The branchial arches represent the embryological precursors of the face, neck and pharynx. Anomalies of the branchial arches are the second most common congenital lesions of the head and neck in children. They may present as cysts, sinus tracts, fistulae or cartilaginous remnants and present with typical clinical and radiological patterns dependent on which arch is involved.

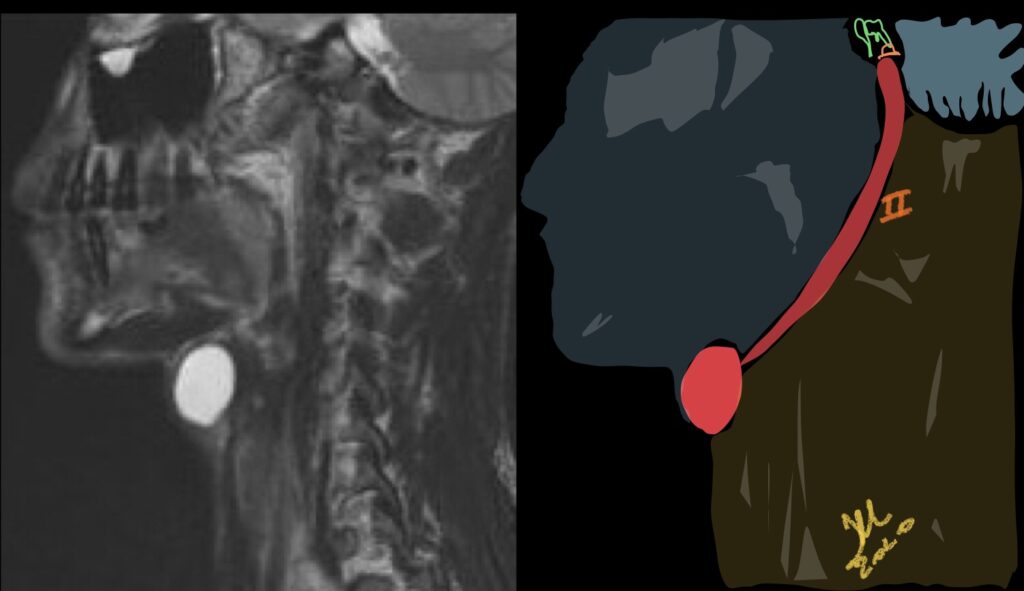

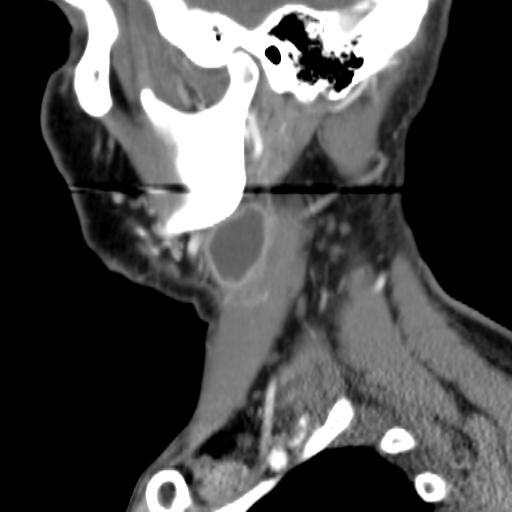

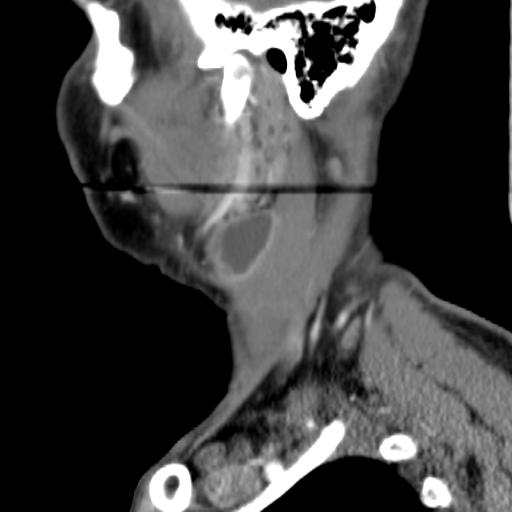

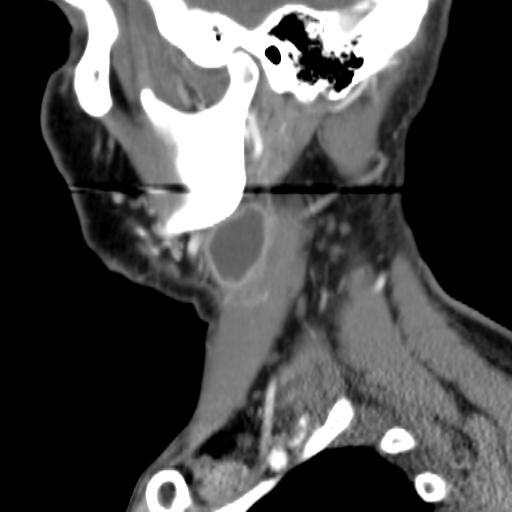

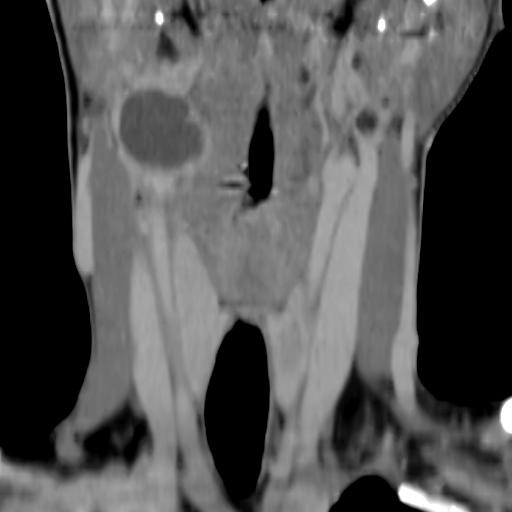

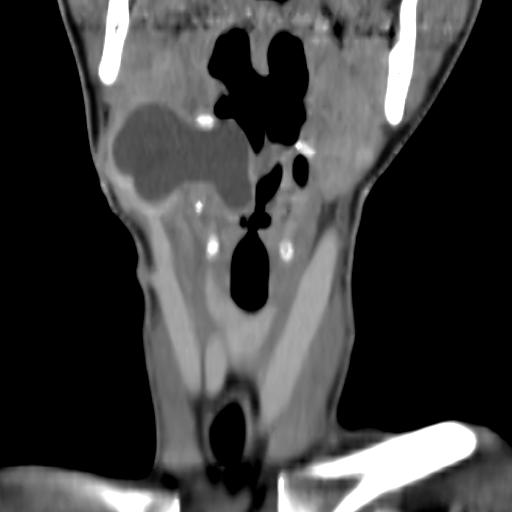

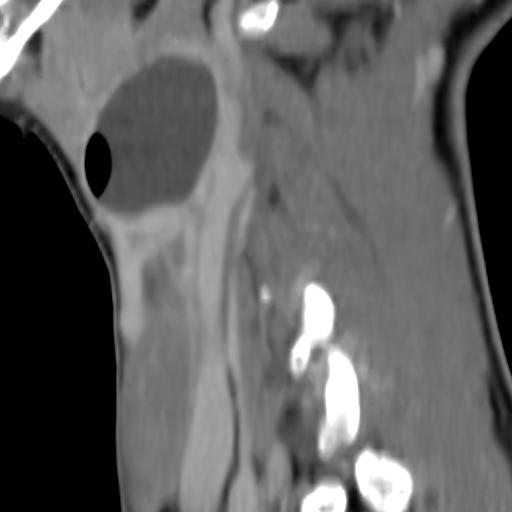

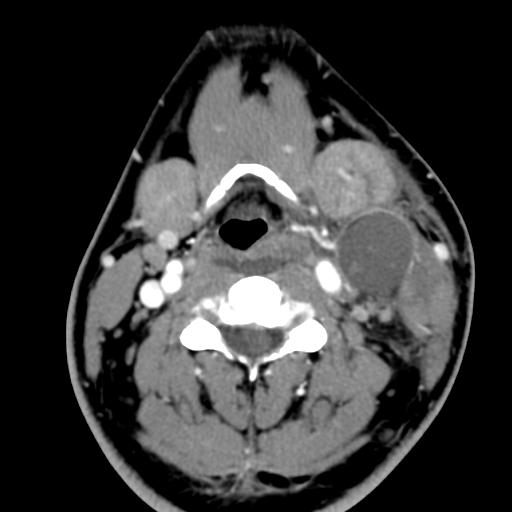

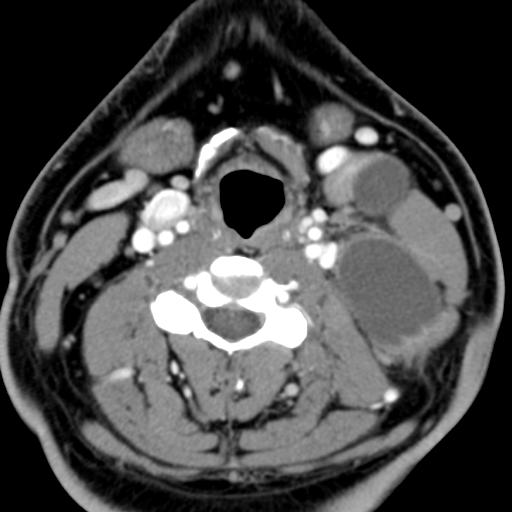

Second branchial cleft anomalies most commonly present as cysts followed by sinuses and fistulae. Most are present within the submandibular space but they can occur anywhere along the course of the second branchial arch tract which extends from the skin overlying the supraclavicular fossa, between the internal and external carotid arteries, to enter the pharynx at the level of the tonsillar fossa. They have previously been classified into four different subtypes by Bailey in 1929:

- Type I – Most superficial and lies along the anterior surface of sternocleidomastoid deep to the platysma, but not in contact with the carotid sheath.

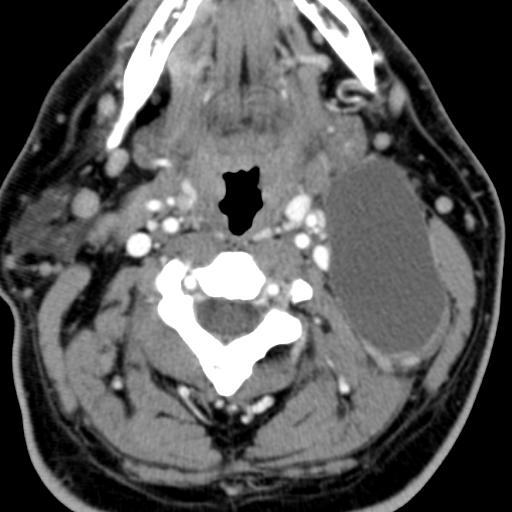

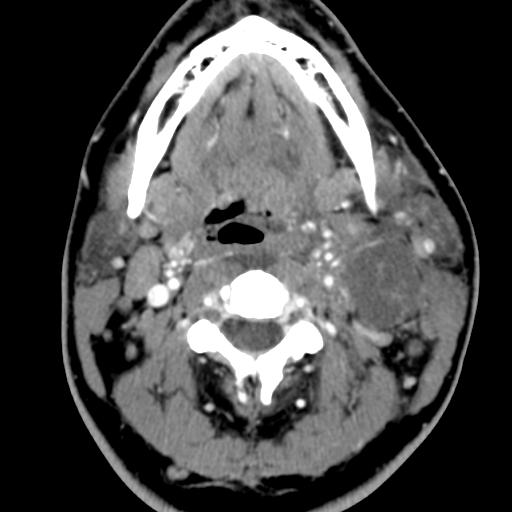

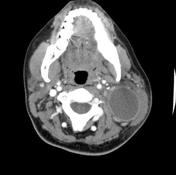

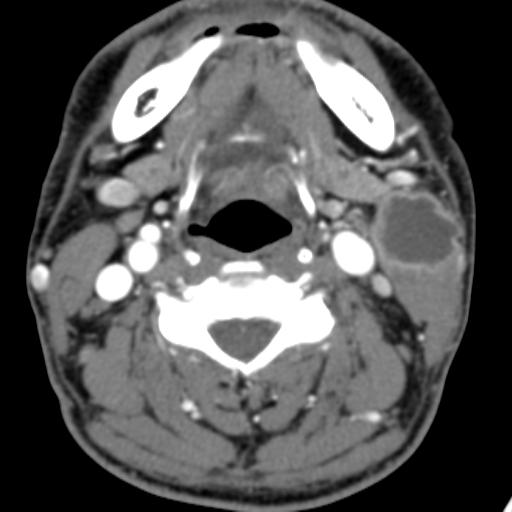

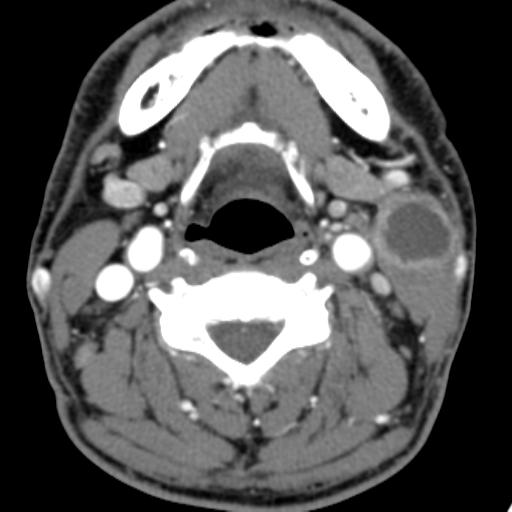

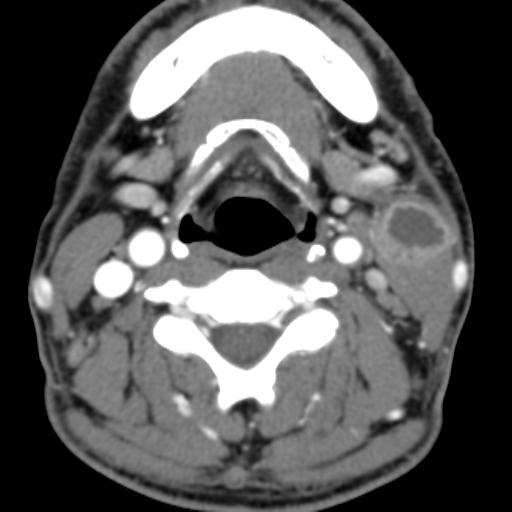

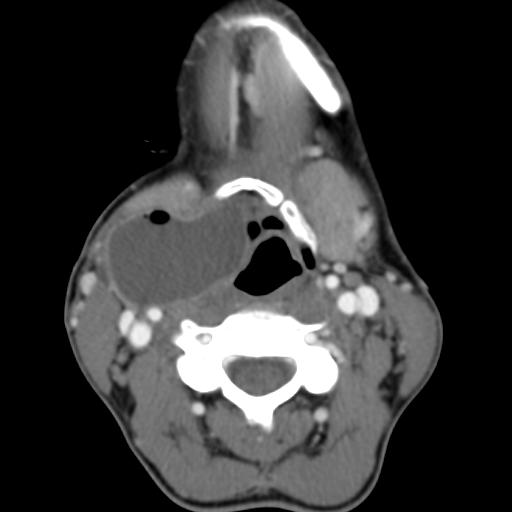

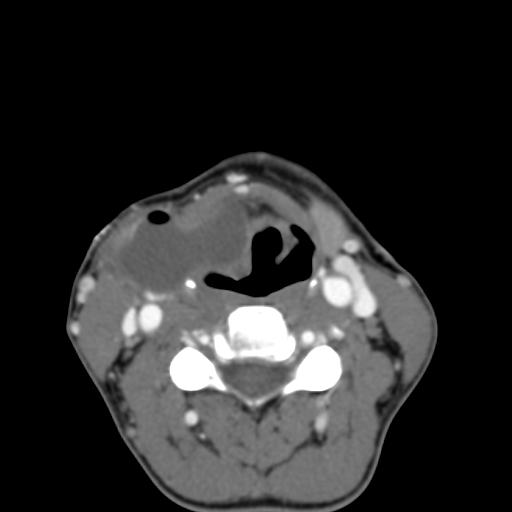

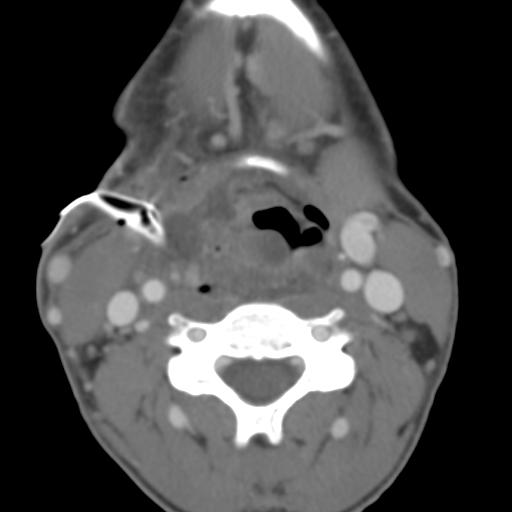

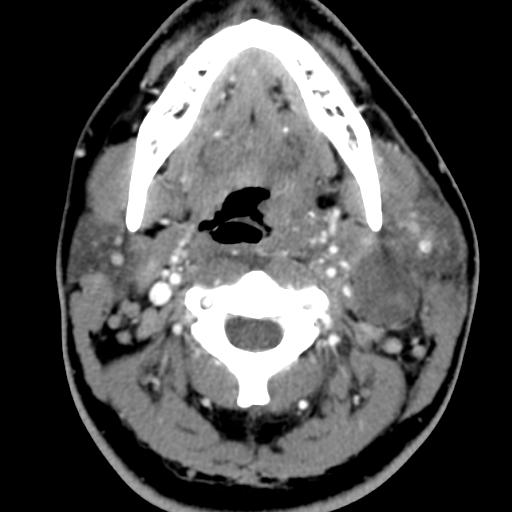

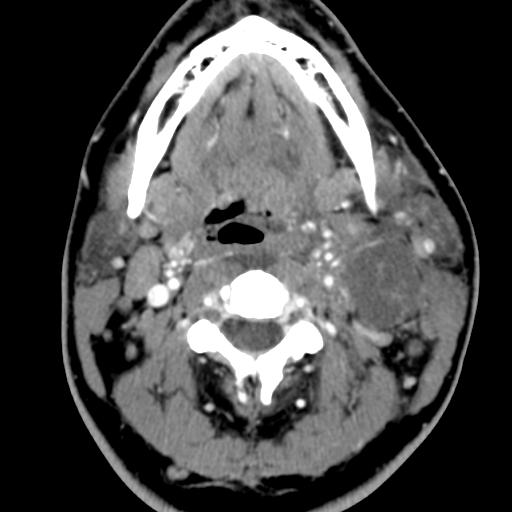

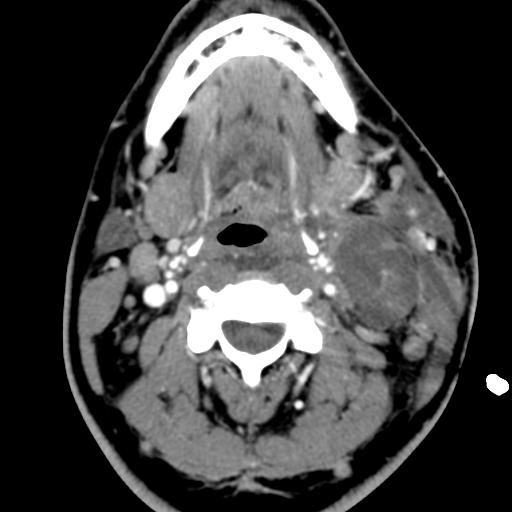

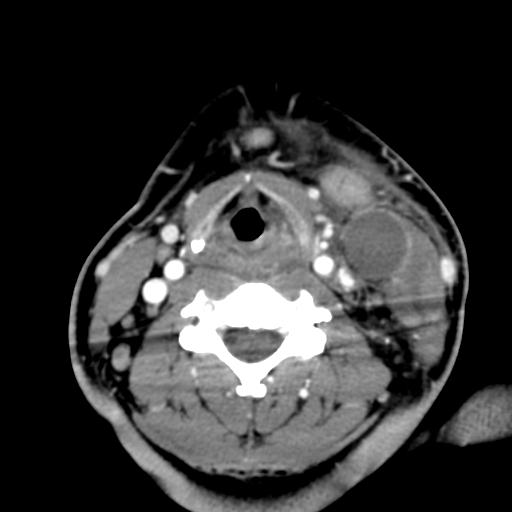

- Type II – Most common type where the branchial cleft cyst lies anterior to the sternocleidomastoid muscle, posterior to the submandibular gland, adjacent and lateral to the carotid sheath.

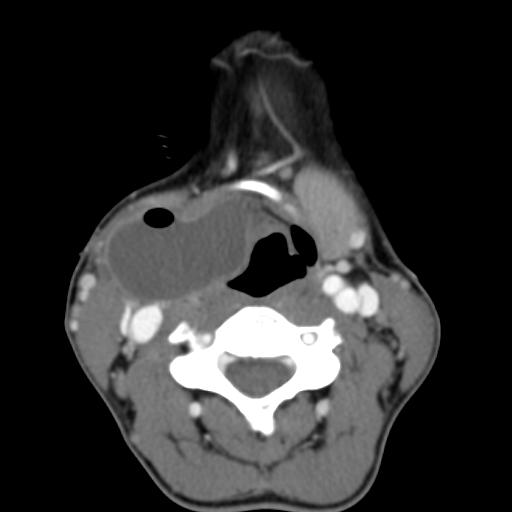

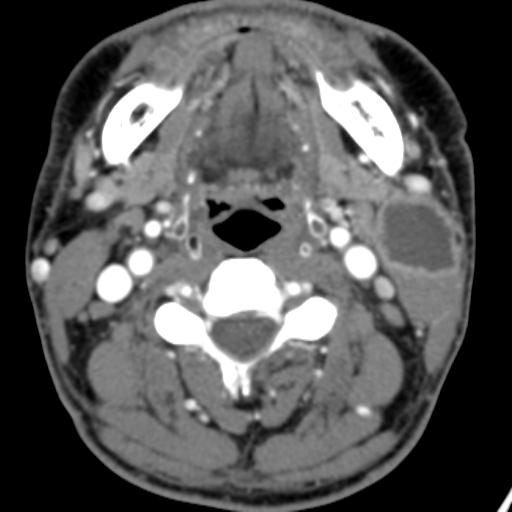

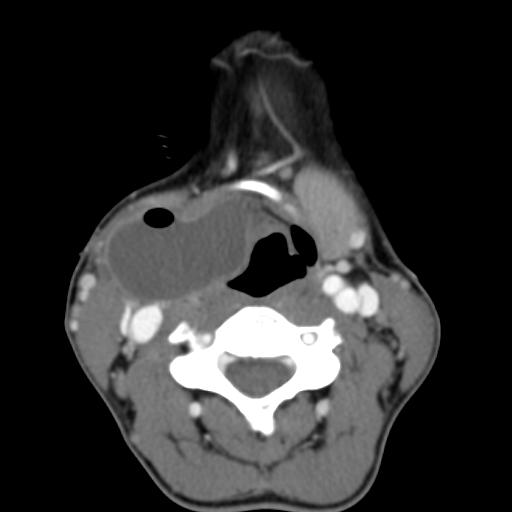

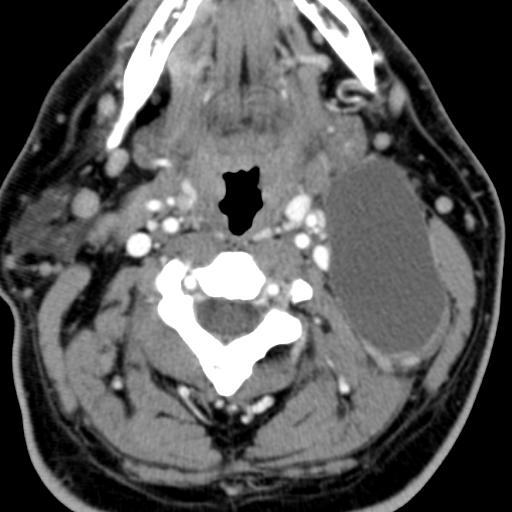

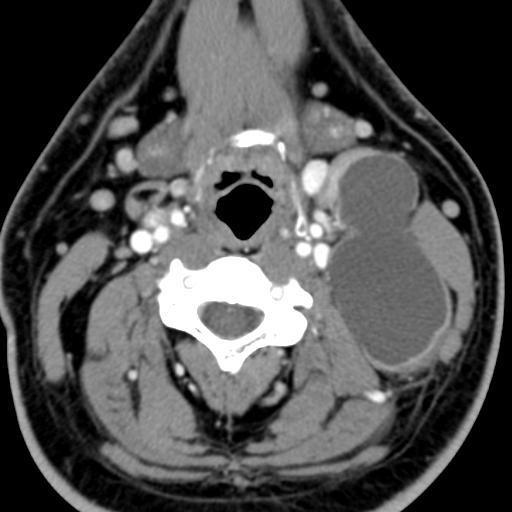

- Type III – Extends medially between the bifurcation of the internal and external carotid arteries, lateral to the pharyngeal wall.

- Type IV- Lies deep to the carotid sheath within the pharyngeal mucosal space and opens into the pharynx.

In adult patients, the main diagnostic consideration is whether the cystic lesion represents a metastatic lymph node and subsequent imaging is directed at identifying a primary neoplastic lesion. This is particularly true if there is no history of chronic neck fullness and no history of a recurrent mass following upper respiratory tract infections. Occult papillary thyroid cancer is also a recognised cause of cystic metastases and may also seen seen in children. Fluid aspiration in association with thyroglobulin levels may aid the distinction.

On ultrasound, second branchial cleft cysts are typically well-circumscribed, thin-walled and anechoic with evidence of compressibility and posterior acoustic enhancement. They may contain internal echoes compatible with internal debris.

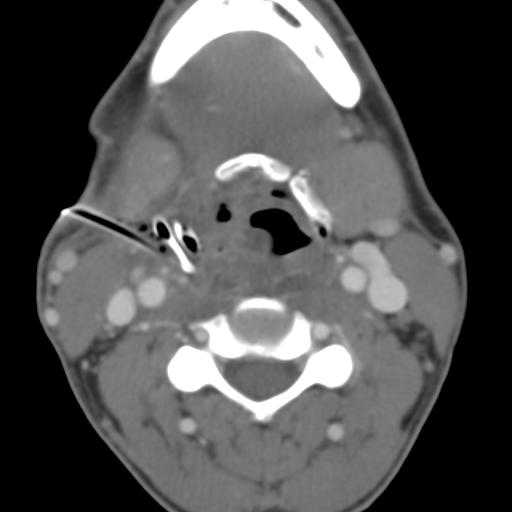

On CT imaging, they are well-circumscribed, low-density cystic masses with a thin wall. If they become infected, this may become thick-walled with evidence of mural enhancement, localised inflammatory change and perilesional fat stranding. The mural thickening is attributed to the response of lymphoid tissue.

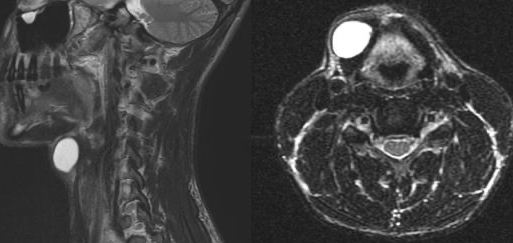

MRI is better suited in the assessment of deep tissue involvement. On T1-weighted imaging, they may turn from low to high signal depending on the proteinaceous content of the cyst, but are typically hyperintense on T2. As with CT imaging, mural thickening and enhancement varies with inflammatory change and typically occurs in the setting of infection. A tissue ‘beak’ between the internal and external carotid arteries is pathognomonic of Bailey type III cysts. Surgical management involves complete surgical excision encompassing the external sinus opening with dissection of the sinus tract.

Reference:

Adams, A., Mankad, K., Offiah, C. et al. Branchial cleft anomalies: a pictorial review of embryological development and spectrum of imaging findings. Insights Imaging 7, 69–76 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13244-015-0454-5