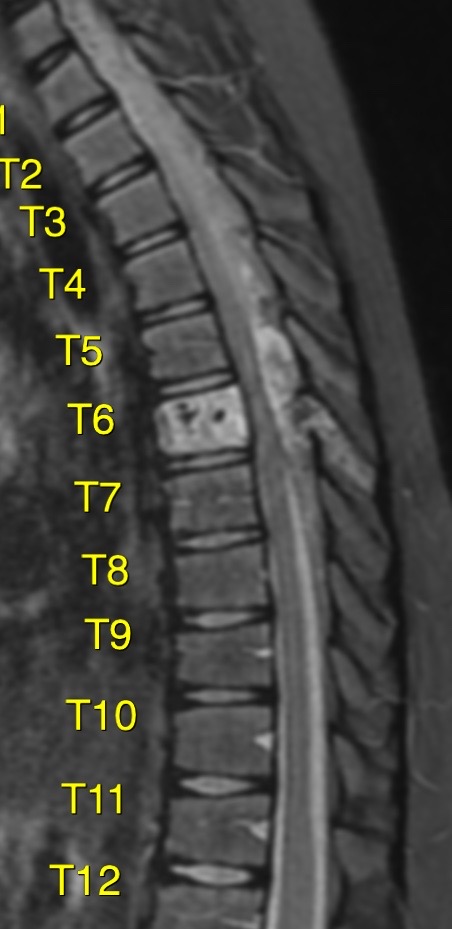

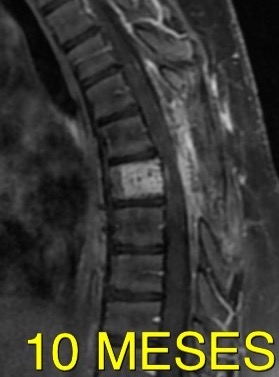

A 13-year-old boy presented with only 3 weeks

duration of progressive ataxia,intense back pain, hypoaesthesia and hyperreflexia of both lower limbs.

Vertebral haemangiomas are the most common tumours of the spine, with an estimated incidence of 10–12% of the population and may occur in the posterior elements, vertebral body or all three columns. Despite its high incidence, only 0.9–1.2% of these are symptomatic in adults.

This figure is much lower in the paediatric population, with a total of 5 cases reported in the literature up to 2011.

Unlike the adult population, the natural course of symptomatic childhood vertebral haemangiomas is highly variable. the reports of vertebral haemangiomas in the paediatric age group have suggested that they tend to behave more aggressively compared to those in adults, whom are known to have slow progressive neurological deficits of an insidious nature.

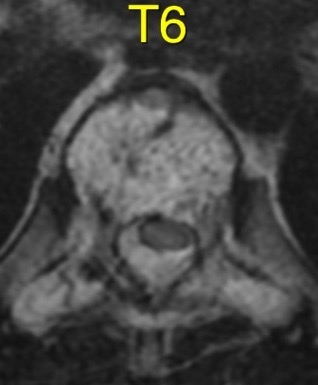

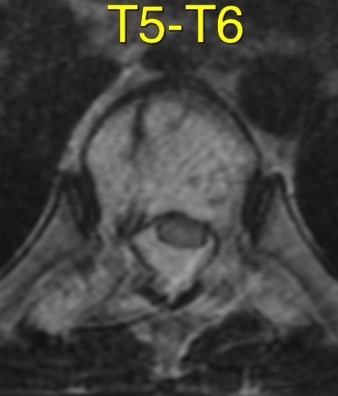

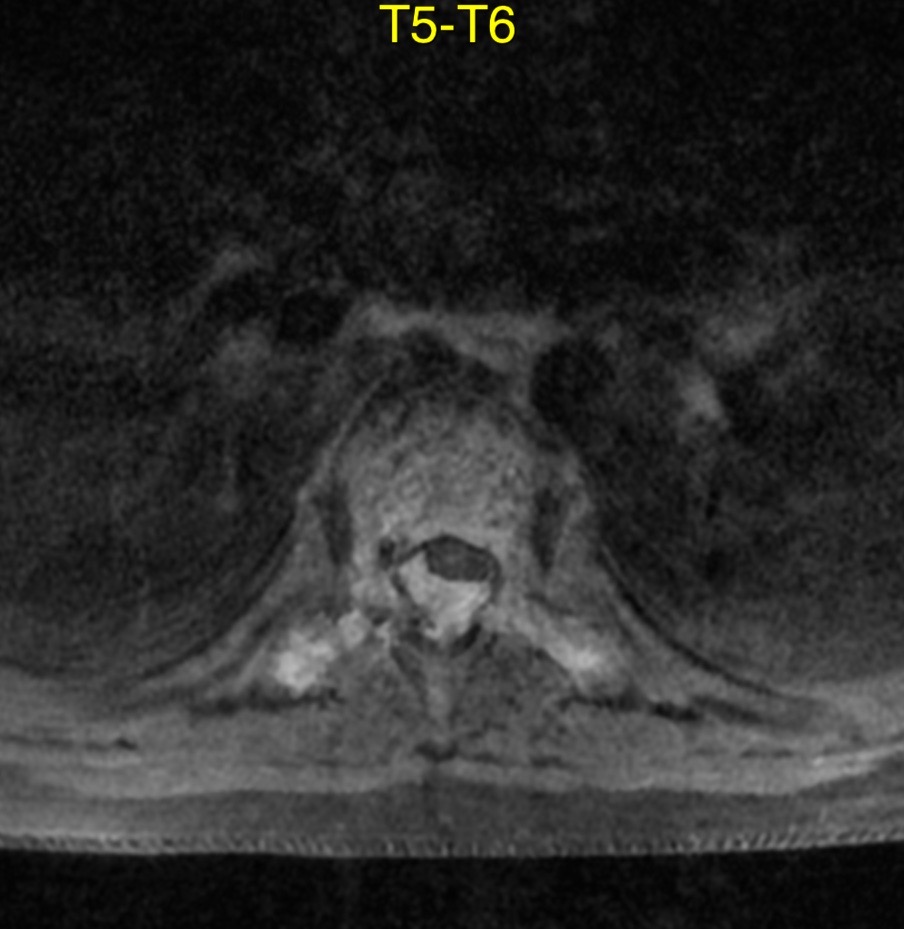

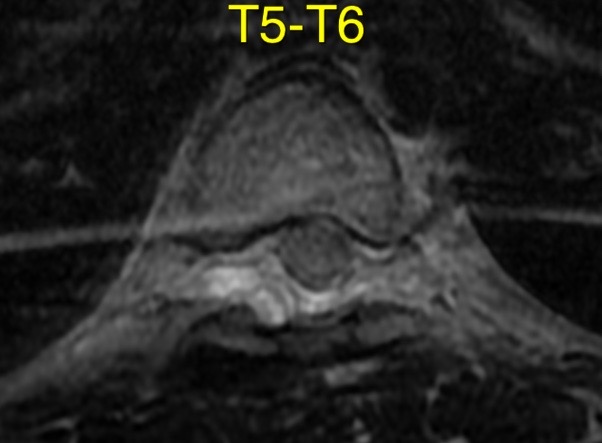

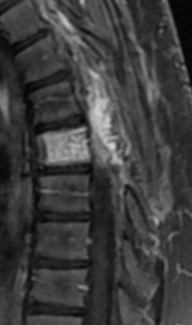

The hyperintense T2 signal is due to the fatty component of the tumour and this allows better differentiation from other highly cellular neoplasms and lymphomas.

Treatment: Surgery in cases of rapid or progressive neurologic symptoms: compressive myelopathy or radiculopathy

Radiotherapy for patients with slow progressive neurologic deficits

Recently, there has been increasing interest in the management of symptomatic lesions using vertebroplasty, transarterial embolization, and direct intralesional ethanol injection

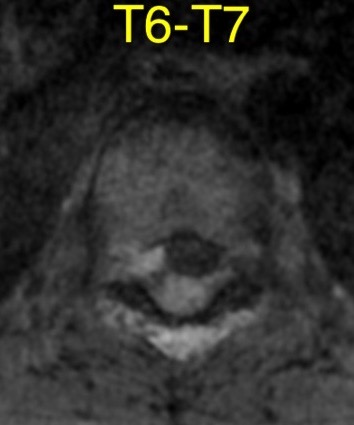

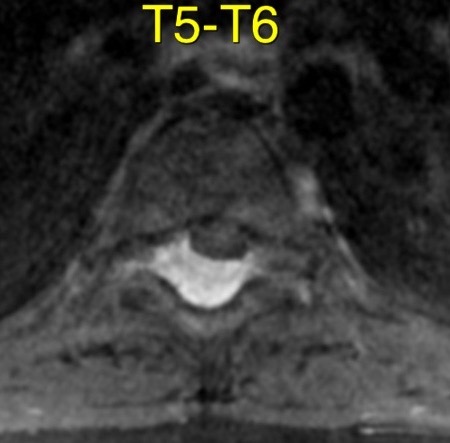

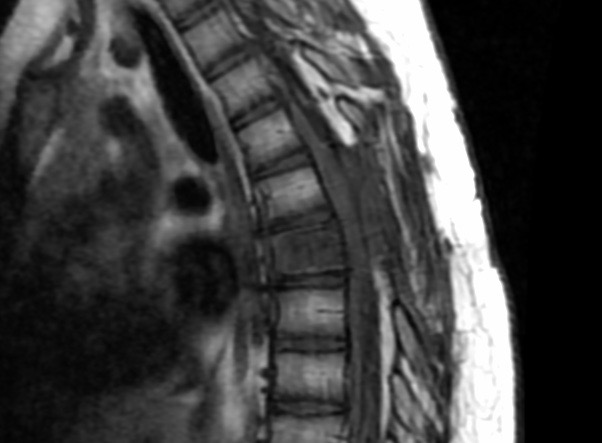

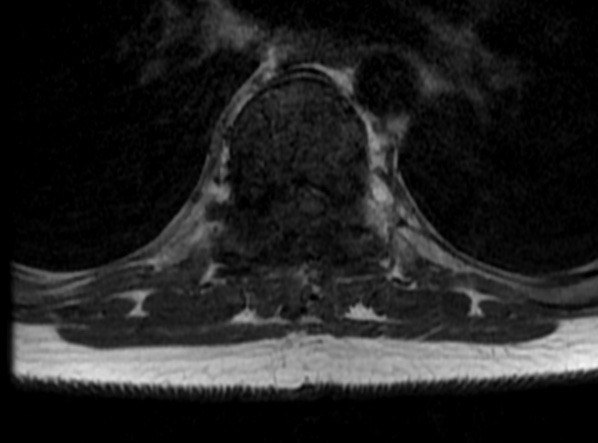

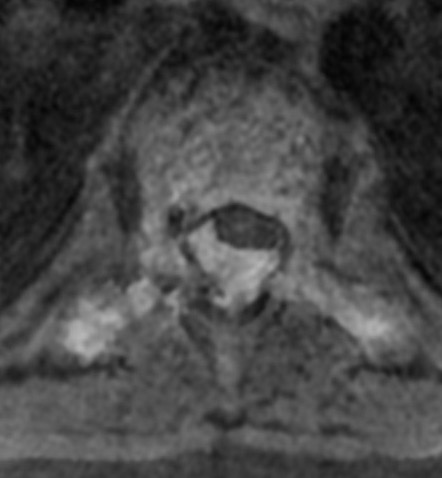

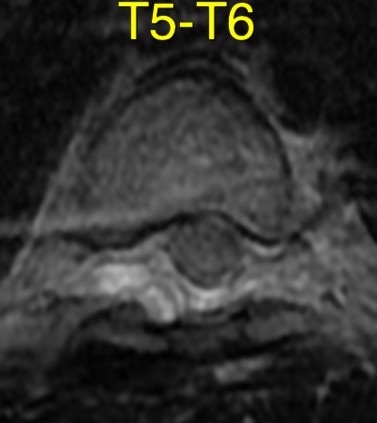

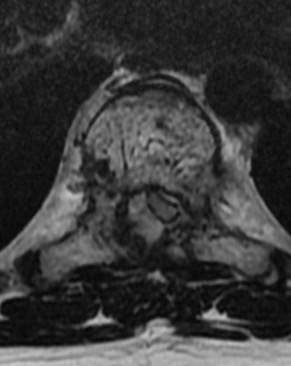

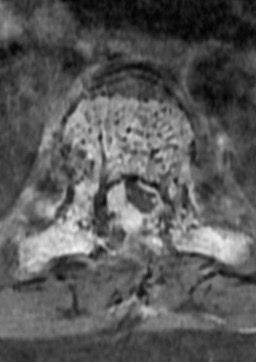

Hemangiomas can be classified as typical, atypical and aggressive (compressive). These are benign tumors composed of capillary-sized to cavernous blood vessels. The term aggressive refers to the presence of radiologic features such as extension beyond the vertebral body, destruction of the cortex, and invasion of the epidural and paravertebral spaces.

Aggressive hemangioma can occur at any age, with peak prevalence in young adults, and is localized preferentially in the thoracic spine.

Neurologic symptoms due to compression of the spinal cord, nerve roots, or both, leading to myelopathy and/or radiculopathy

Clinical worsening and growth during pregnancy is a well known phenomenon. The main explanation is vena cava compression and re-routing of blood to the paravertebral, epidural, and acygous venous system.

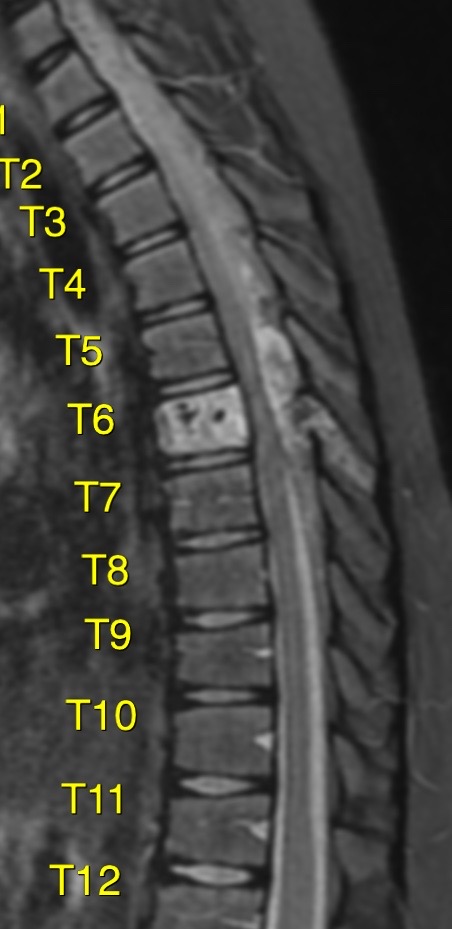

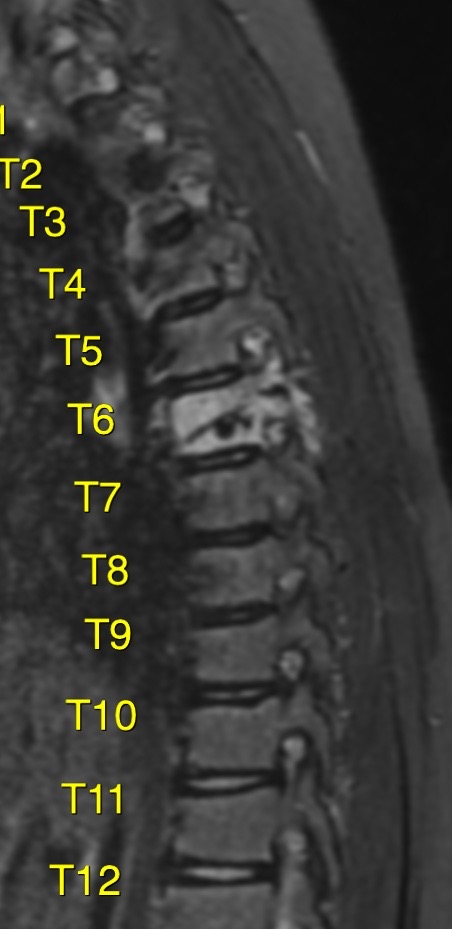

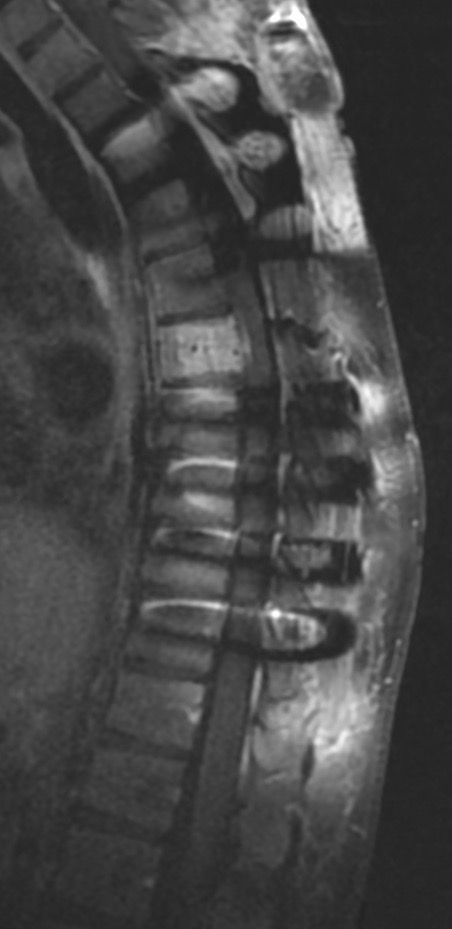

CT scan reveals hypodense expansile vertebral body mass, with soft tissue extension and spinal cord/nerve root compression. Typical «polka-dot» and «corduroy» signs can guide the correct diagnosis.

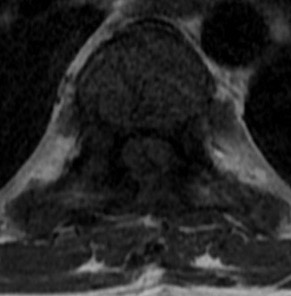

MRI shows a T1 hypointense, high-T2 lesion with variable contrast enhancement. Aggressive hemangiomas are difficult to diagnose by MRI because findings overlap with those of metastatic disease and focal bone marrow infiltration.

Differential Diagnosis:

Metastases: Findings that favor an aggressive hemangioma over a metastasis are maintained vertebral body height, a sharp margin with normal marrow, intact cortex adjacent to a paraspinal mass, enlarged paraespinal vessels, and the «polka dot» sign on axial images.

Solitary bone plasmocytoma: Classically, plasmocytomas can have a «mini brain» appearance on axial CT and MR imaging (thickened cortical struts resemble the sulci seen in the brain) or, less typically, multicystic «soap bubble» appearance.

Lymphoma: The epidural component of a vertebral lymphoma appears less hyperintense on T2W compared with the hypervascular component of aggressive hemangioma.

Epitheloid hemangioendothelioma: Lytic pattern of bone destruction with mixed signal intensity on T1- and T2-weighted MRI due to the absence of fat and the presence of inflammatory infiltrate

Reference:

https://doi.org/10.1007/s00381-011-1391-3

http://www.ajnr.org/ajnr-case-collections-diagnosis/aggressive-spinal-hemangioma