Cervical myelopathy is a condition describing a compression of the spinal cord at the cervical level of the spinal column resulting in spasticity , hyperreflexia, pathologic reflexes, digit/hand clumsiness, and/or gait disturbance. Classically it has an insidious onset progressing in a stepwise manner with functional decline.

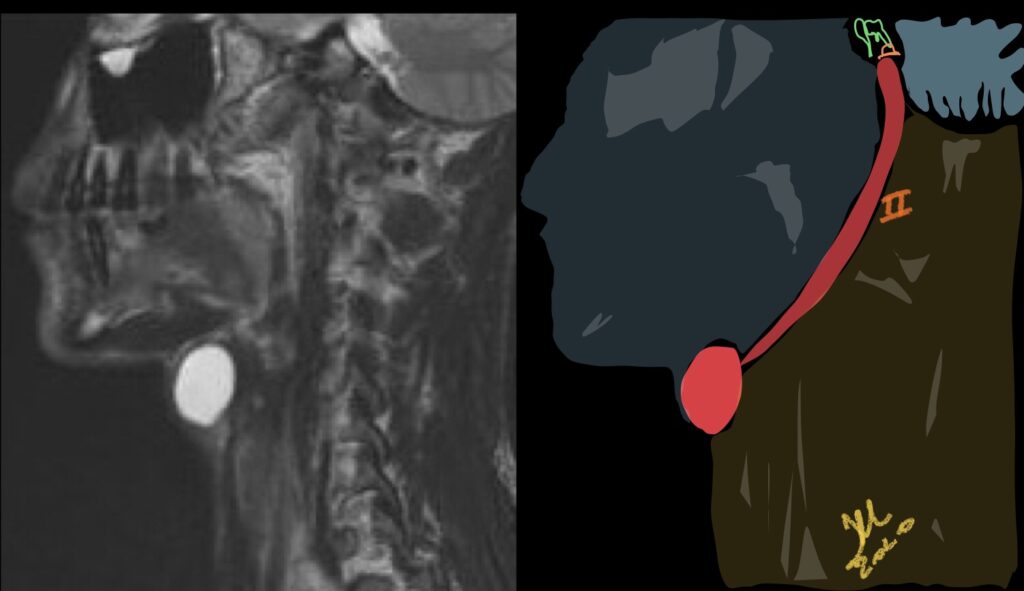

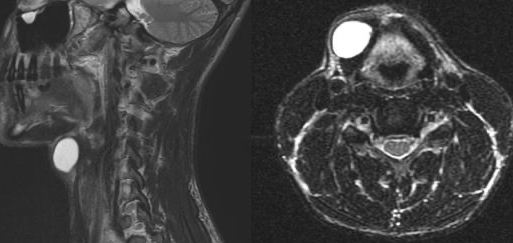

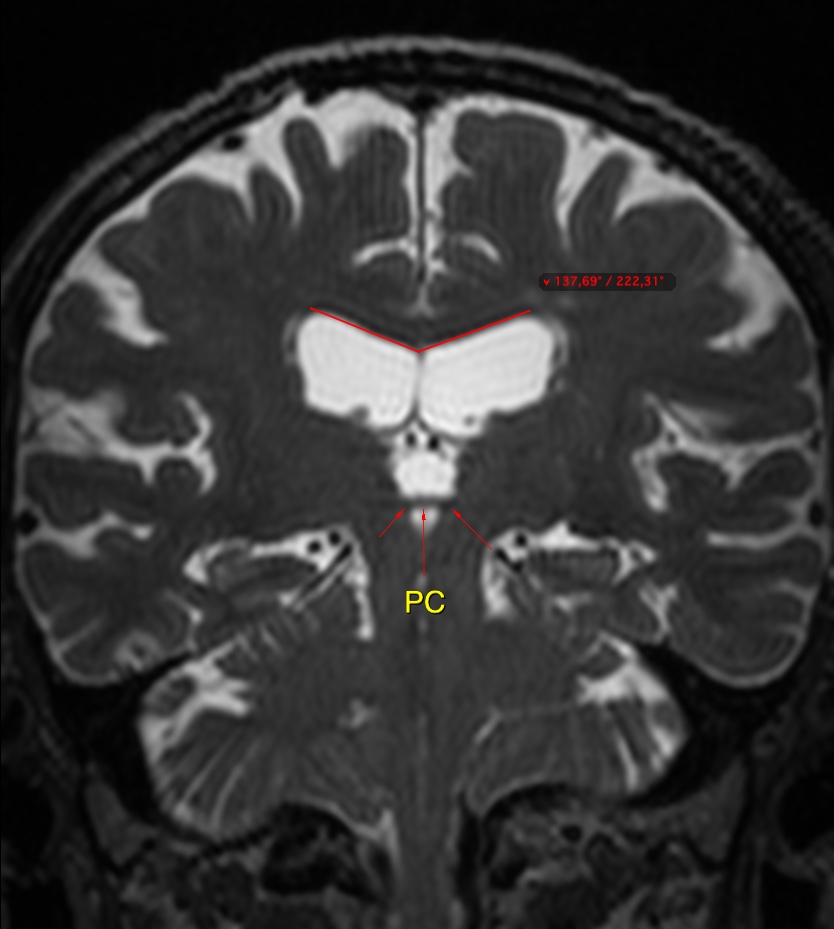

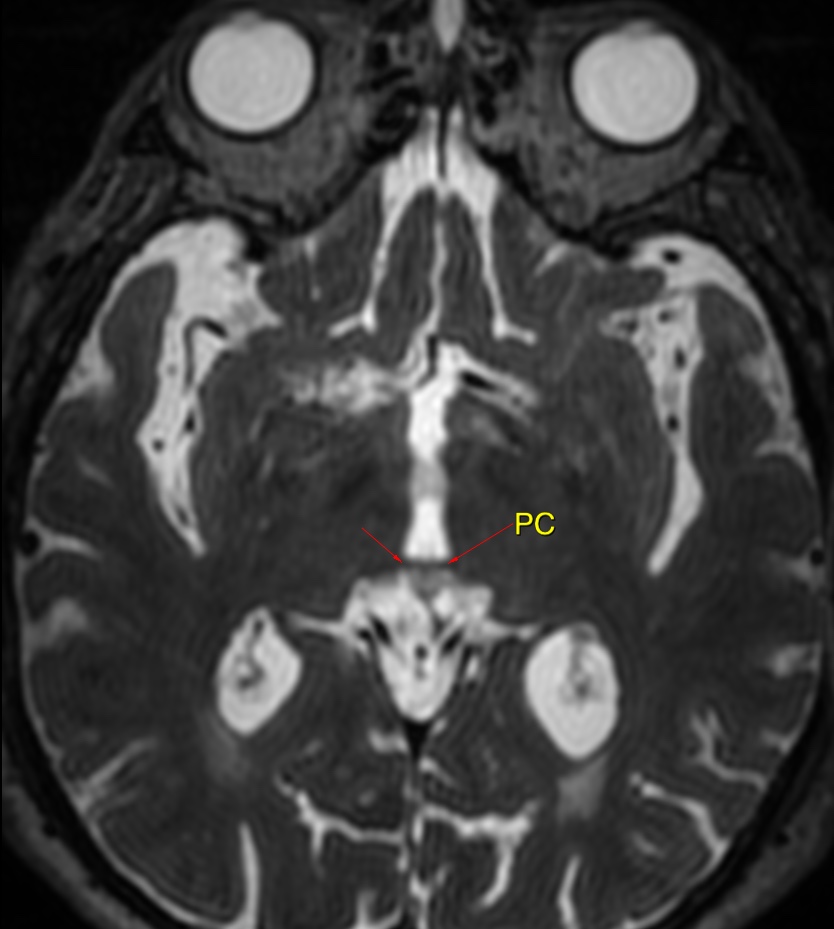

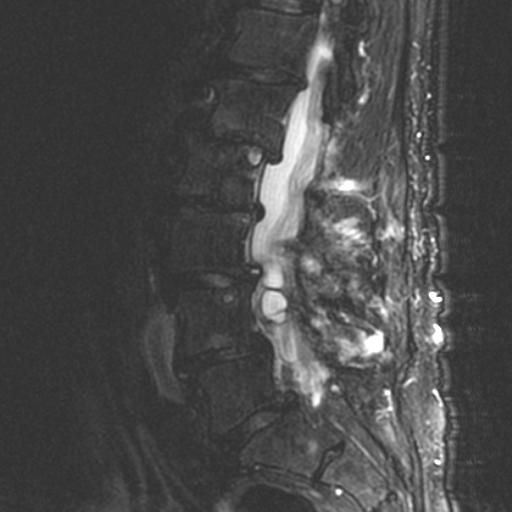

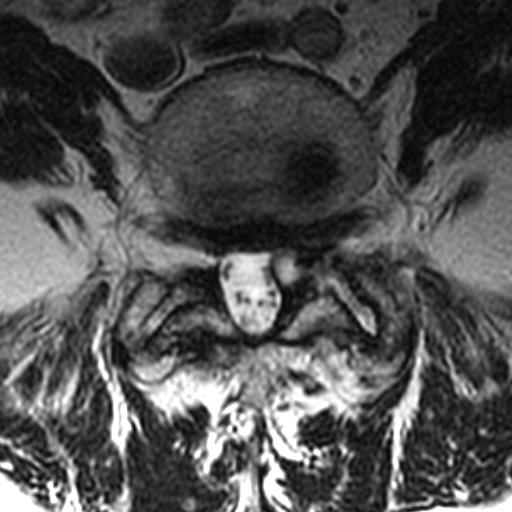

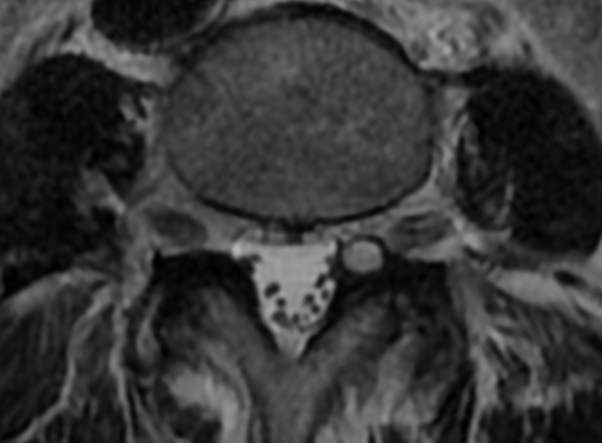

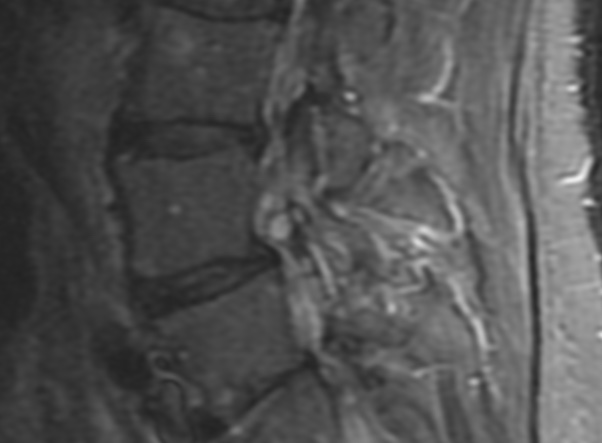

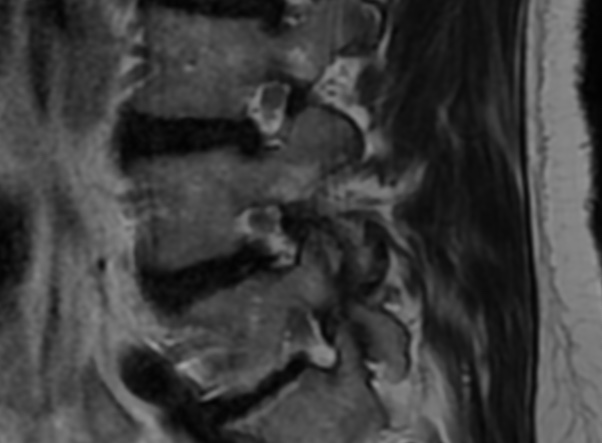

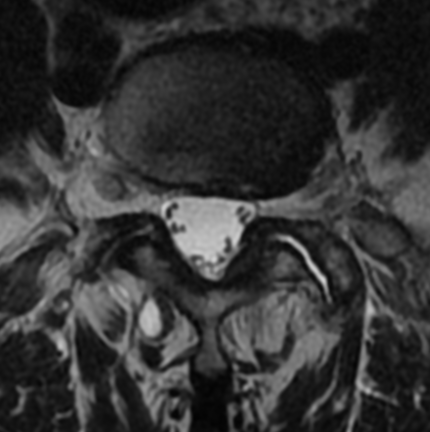

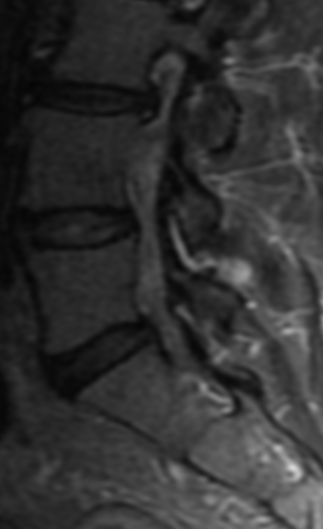

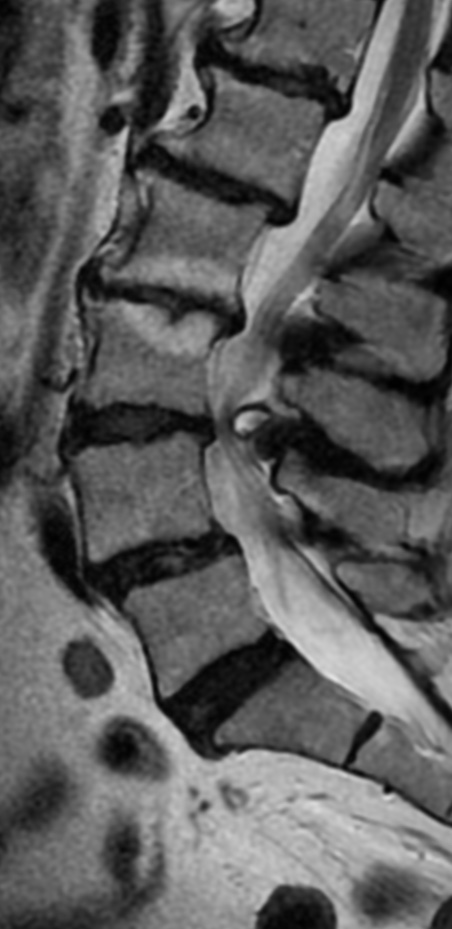

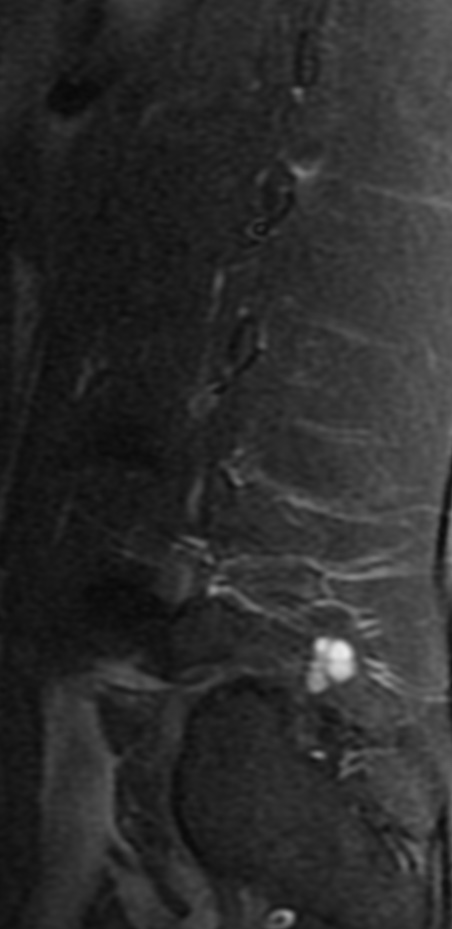

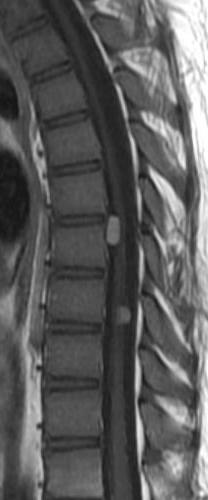

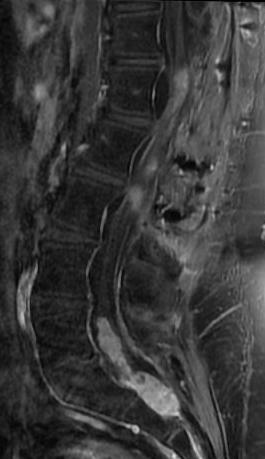

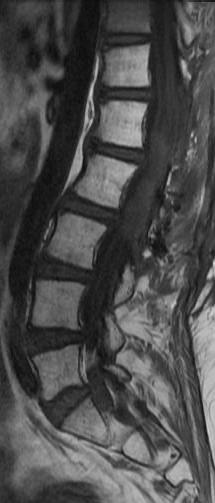

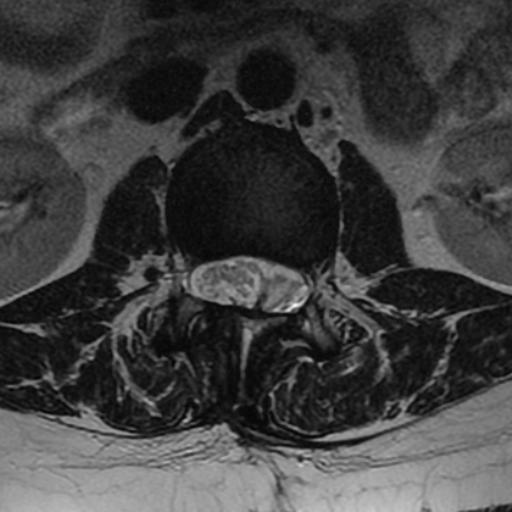

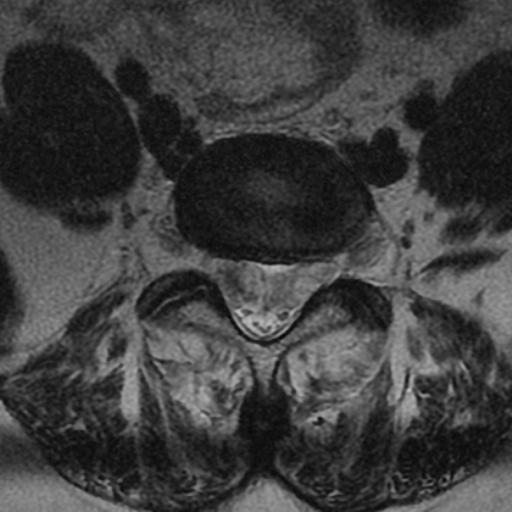

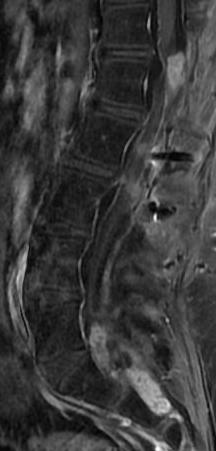

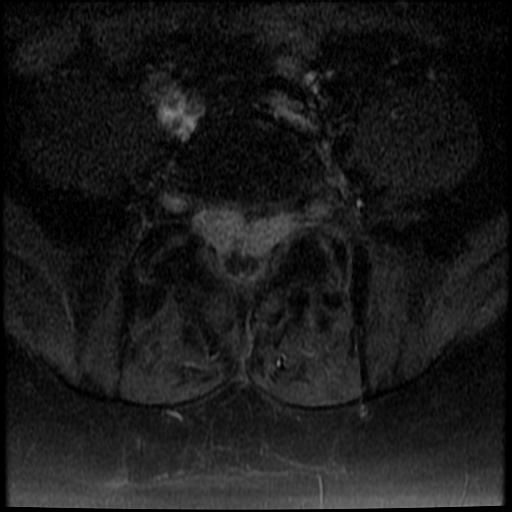

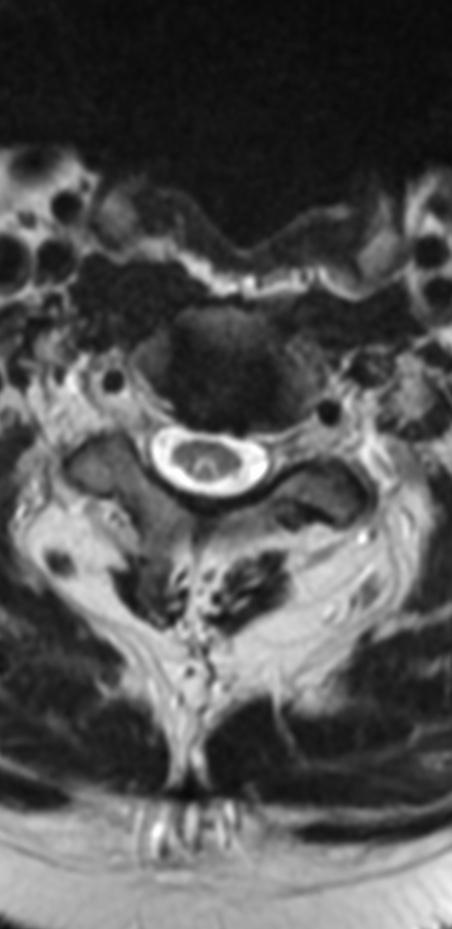

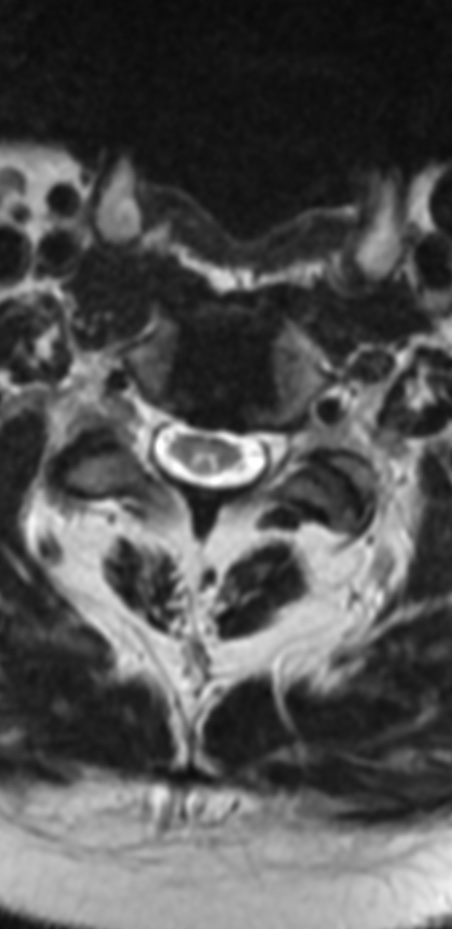

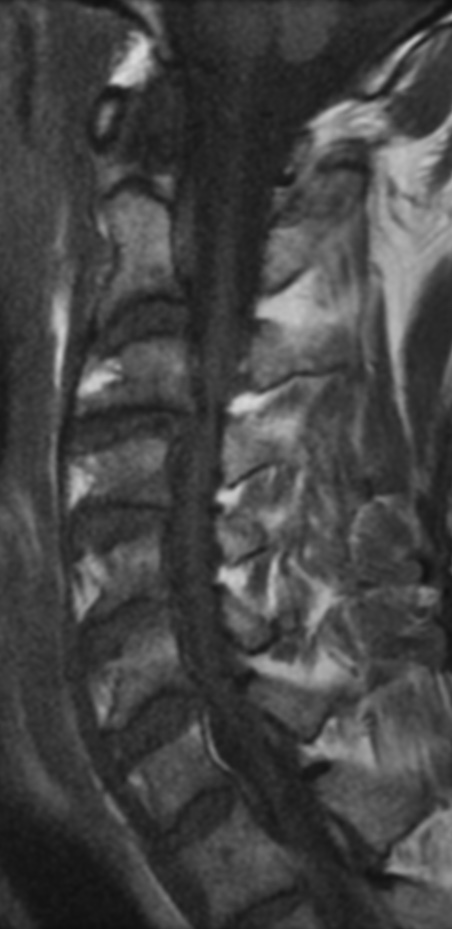

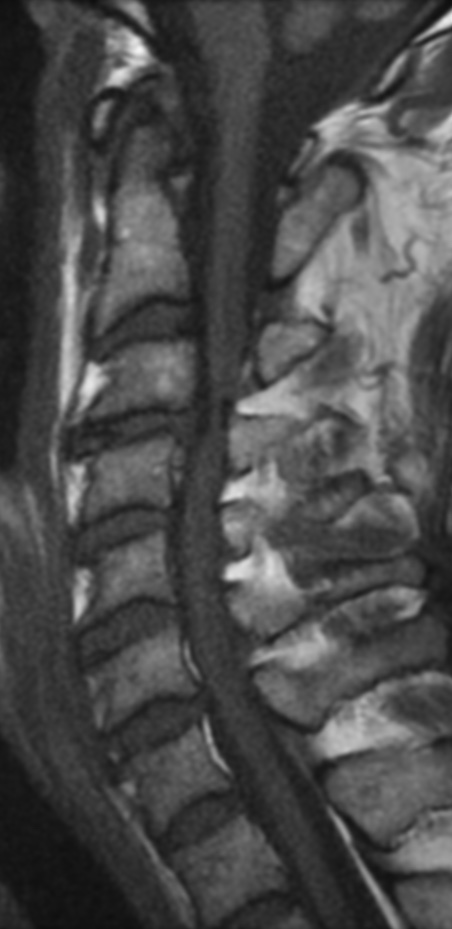

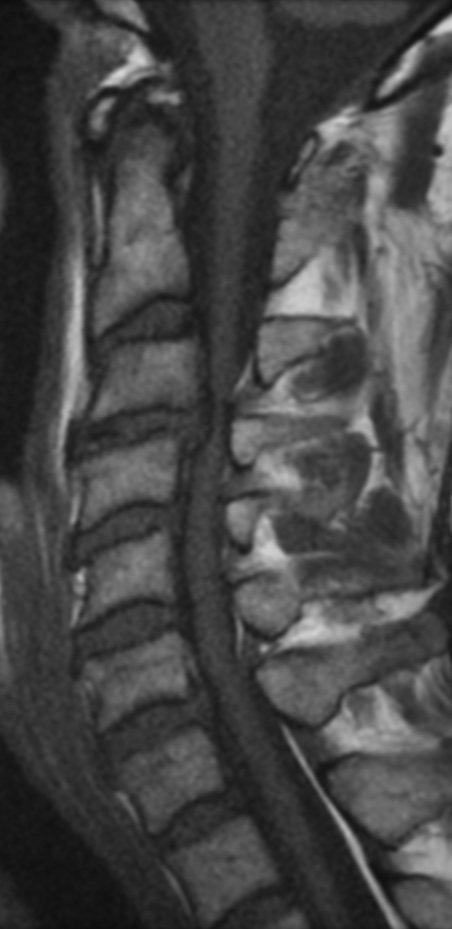

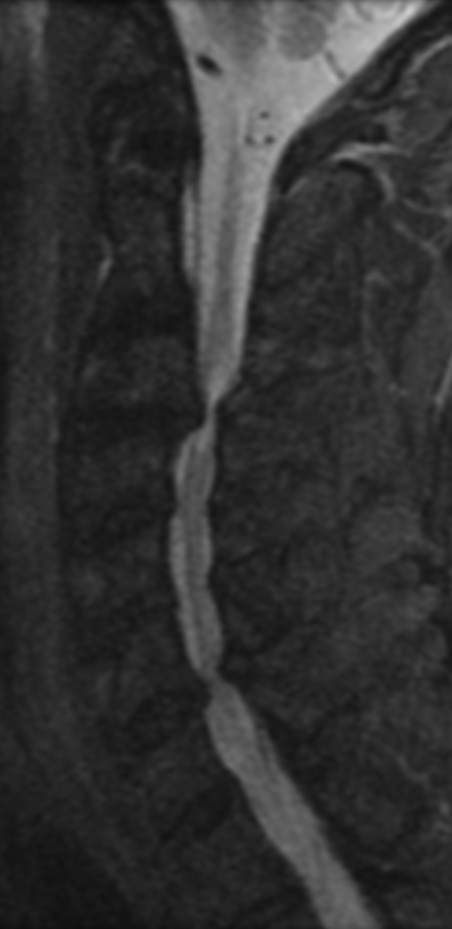

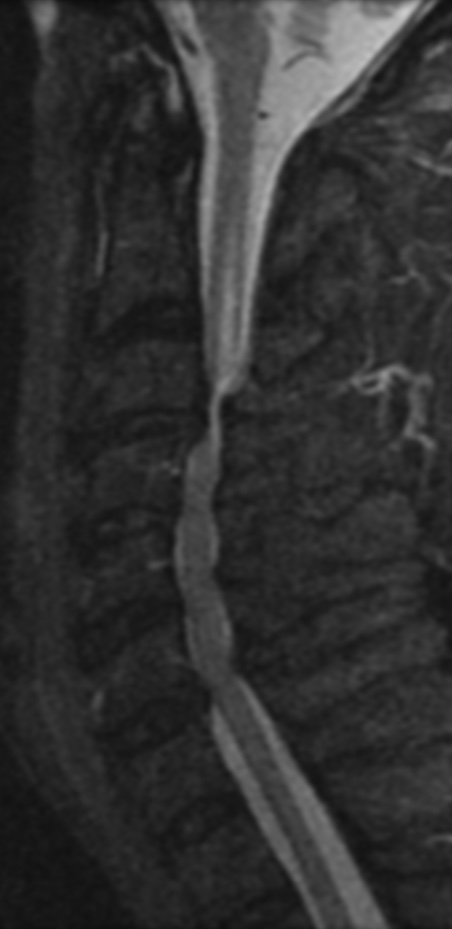

An MRI can provide some guidance for clinicians and patients about the potential for improvement. Based on a systematic review of MRI findings by Tetreault et al. in 2013:

- High-intensity changes on T2 and low intensity on T1: poorer recovery rate, worse motor symptom improvements

- More frequent high signal intensity on T2 predicts worse recovery.

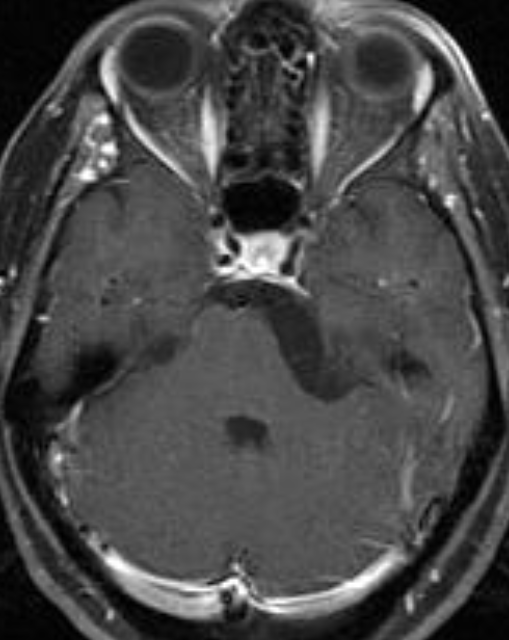

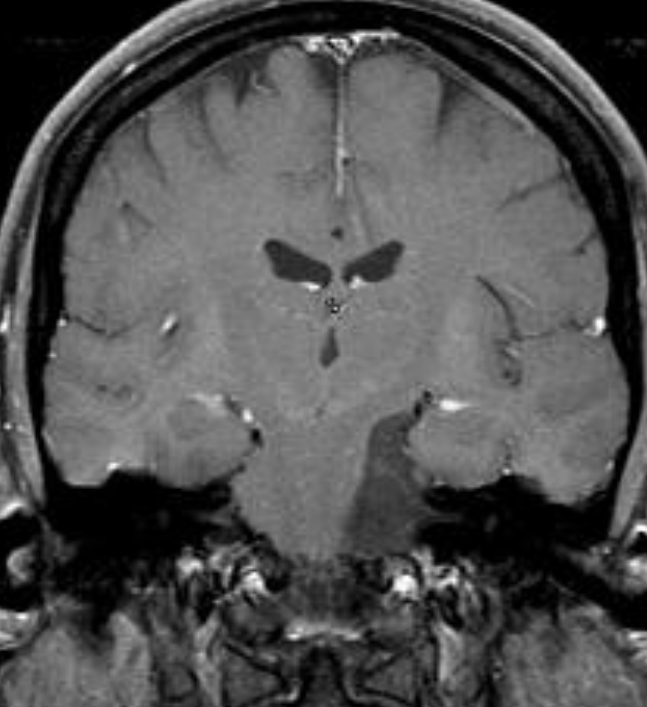

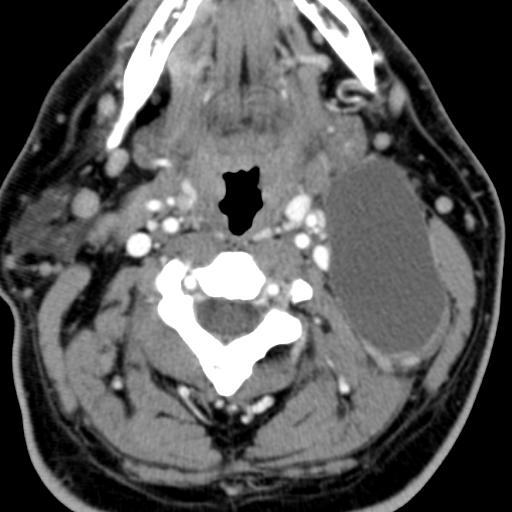

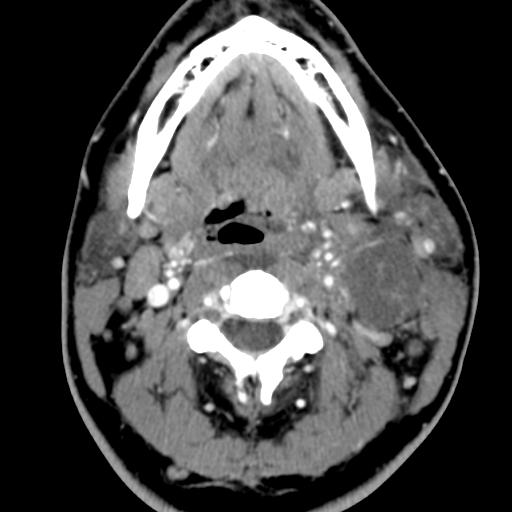

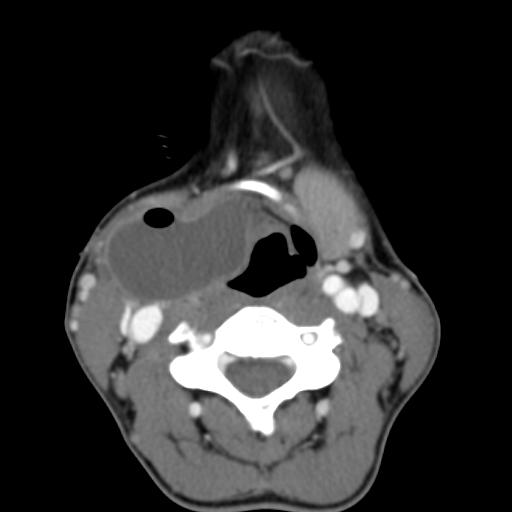

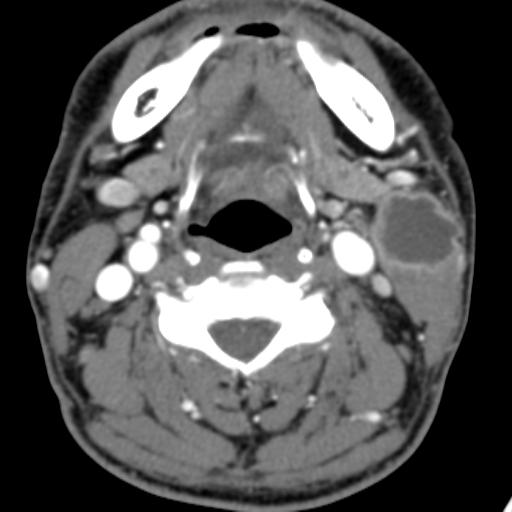

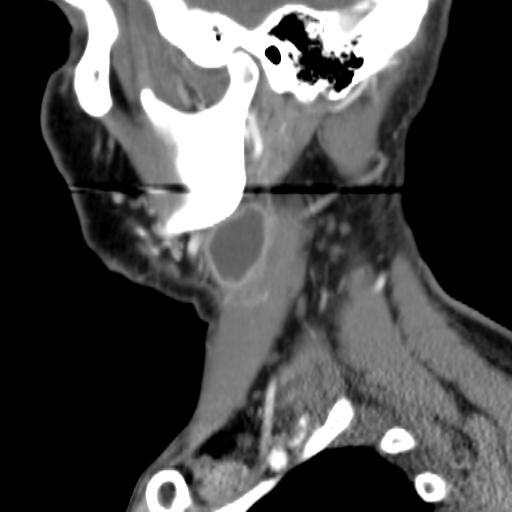

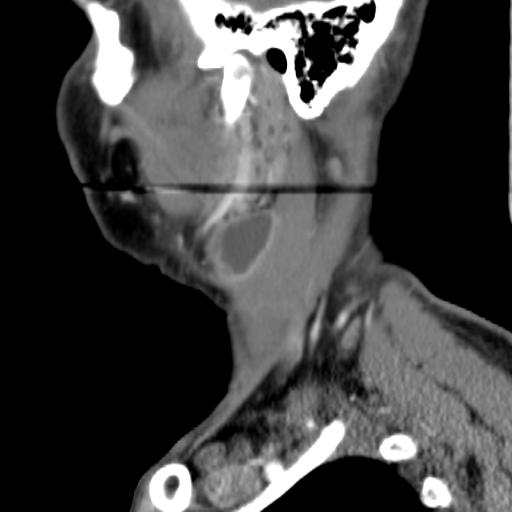

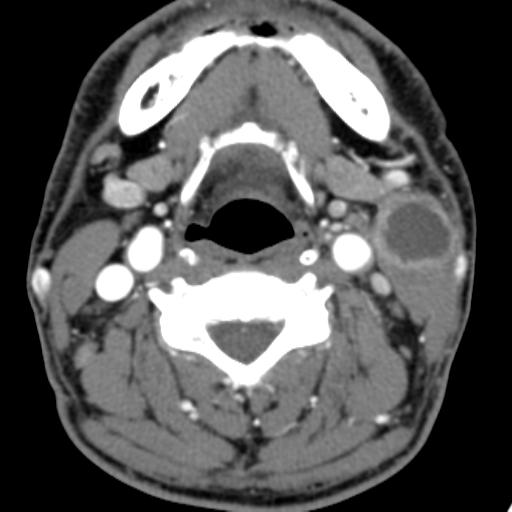

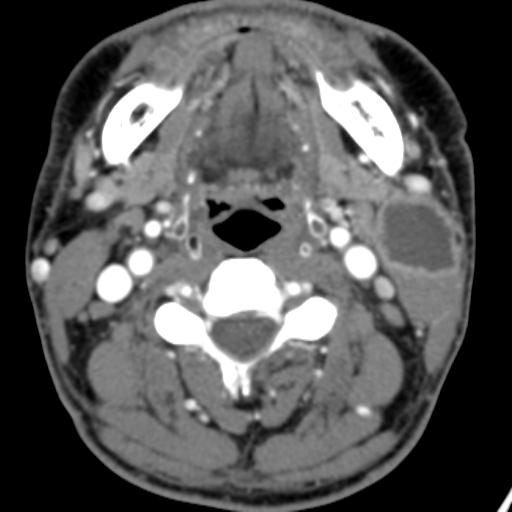

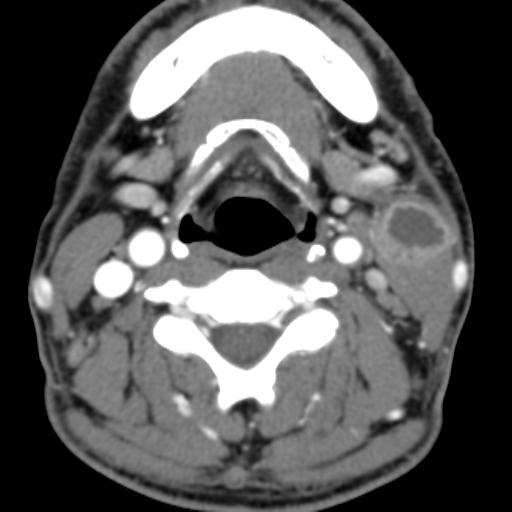

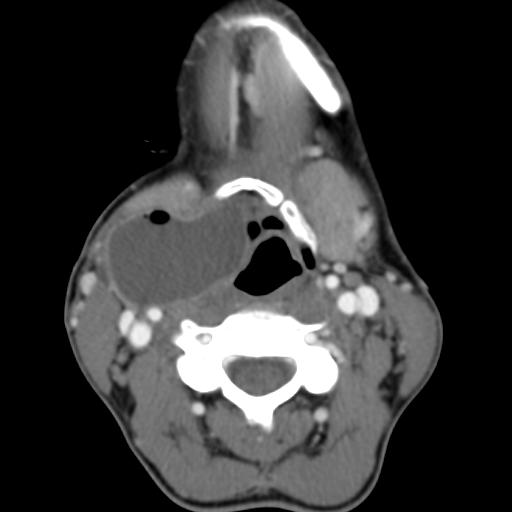

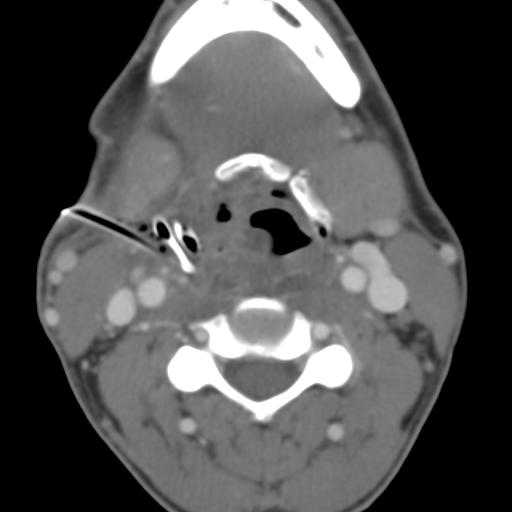

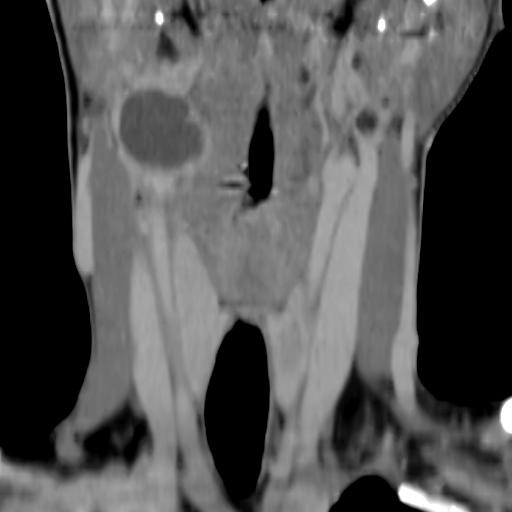

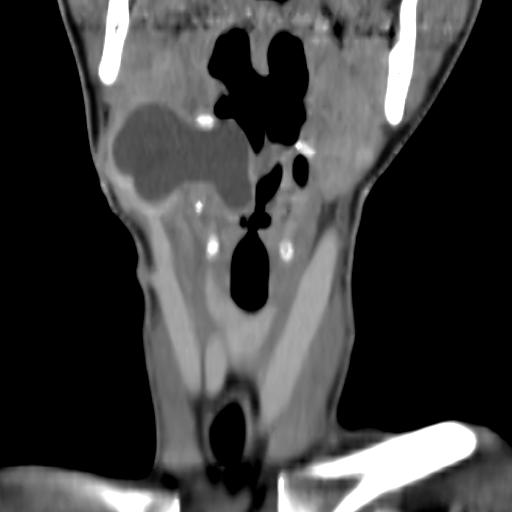

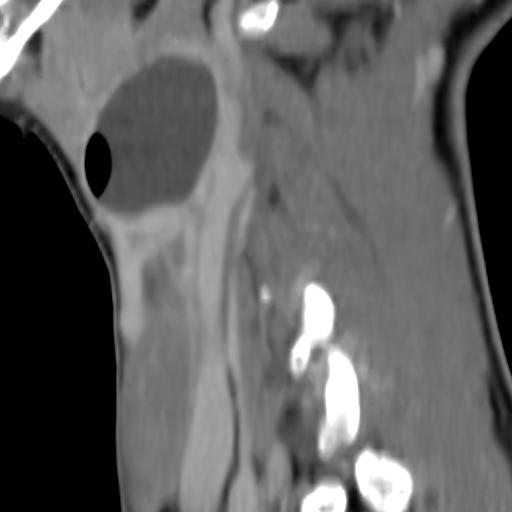

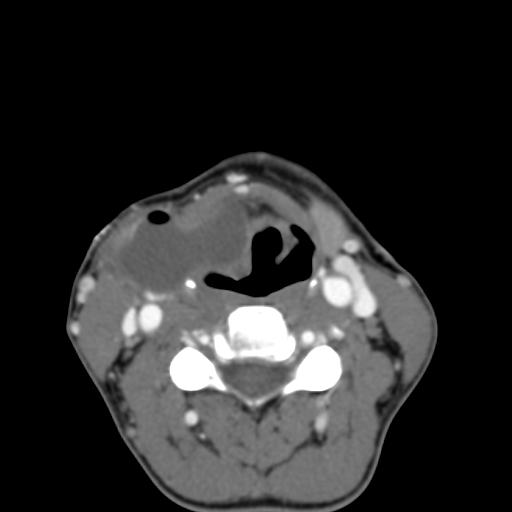

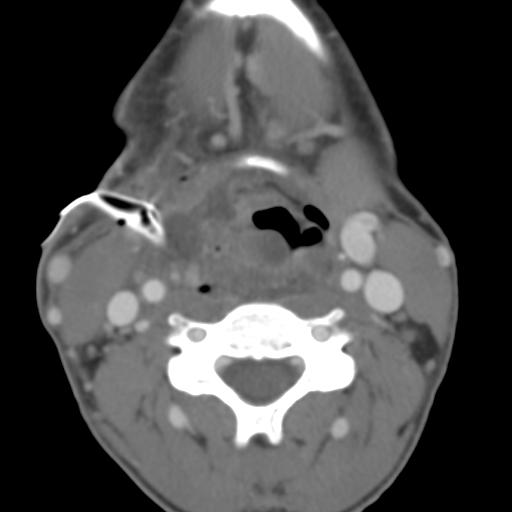

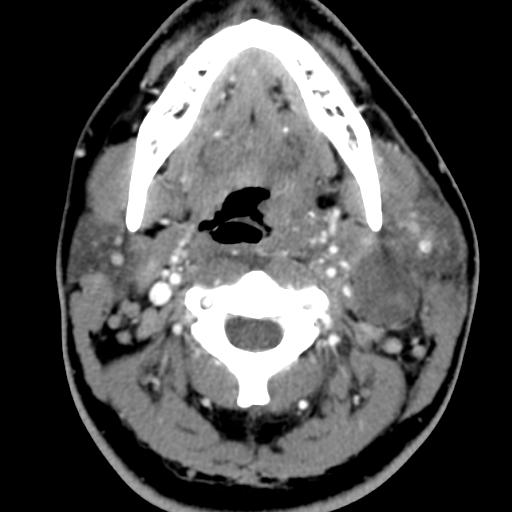

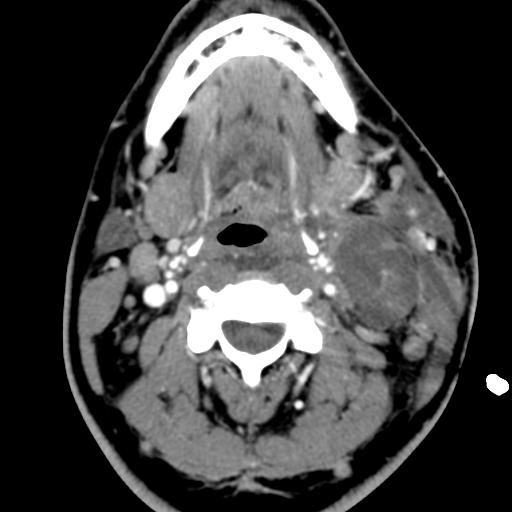

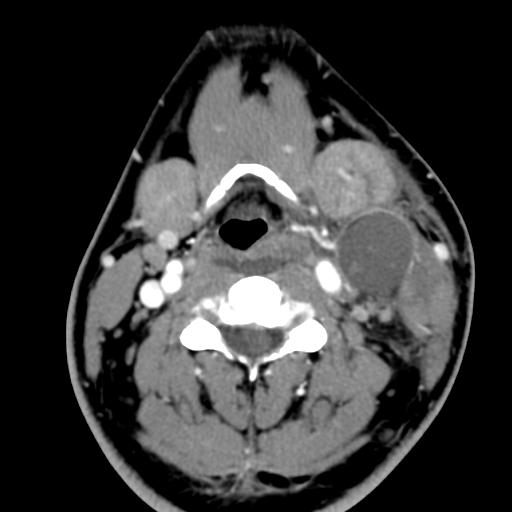

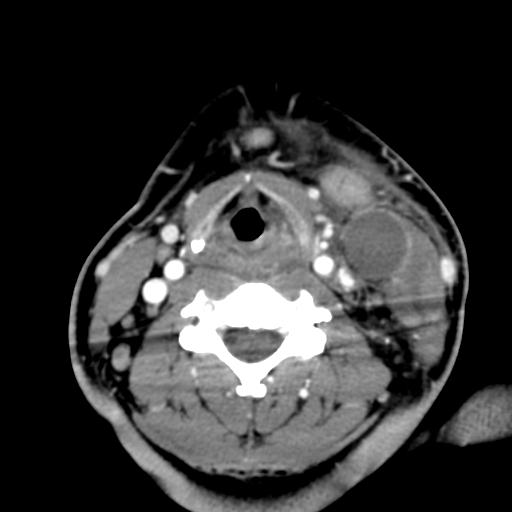

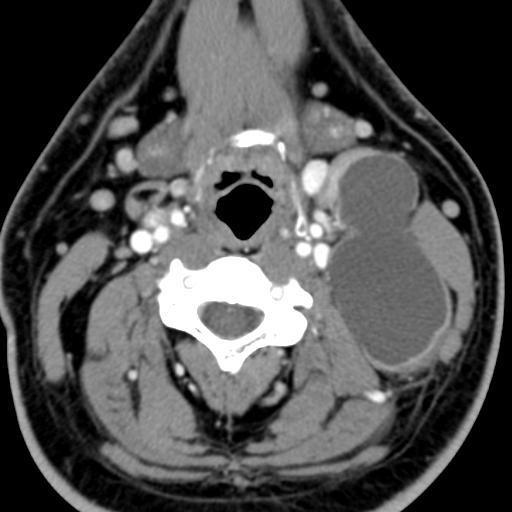

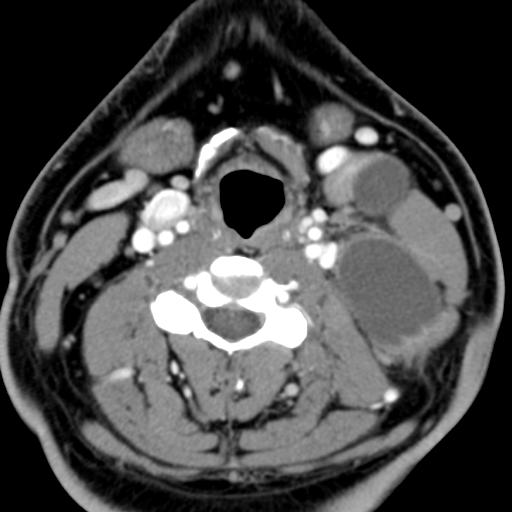

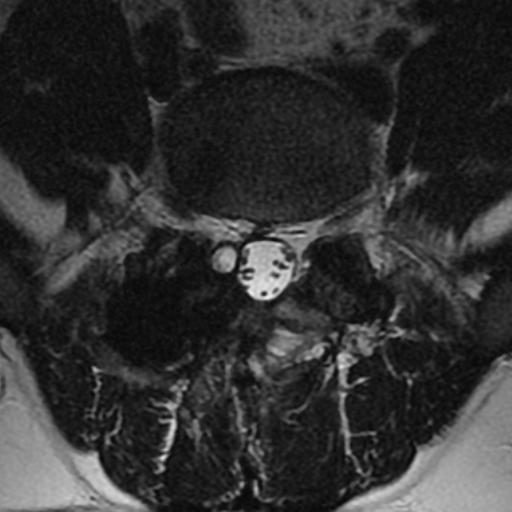

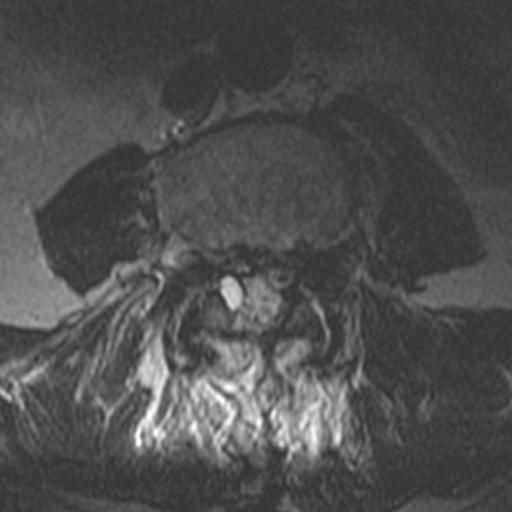

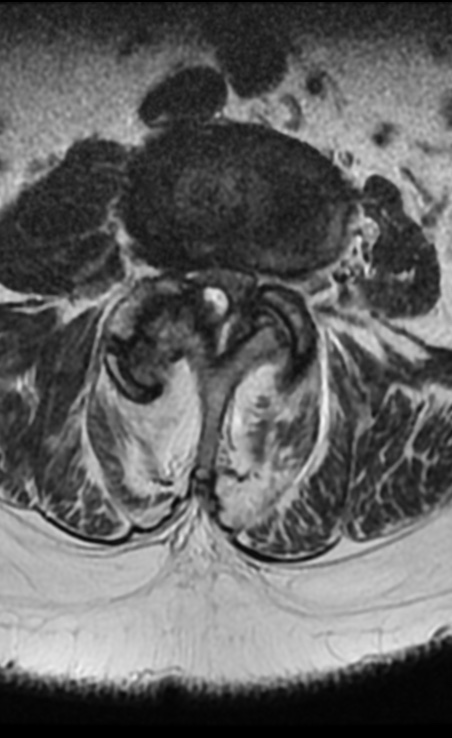

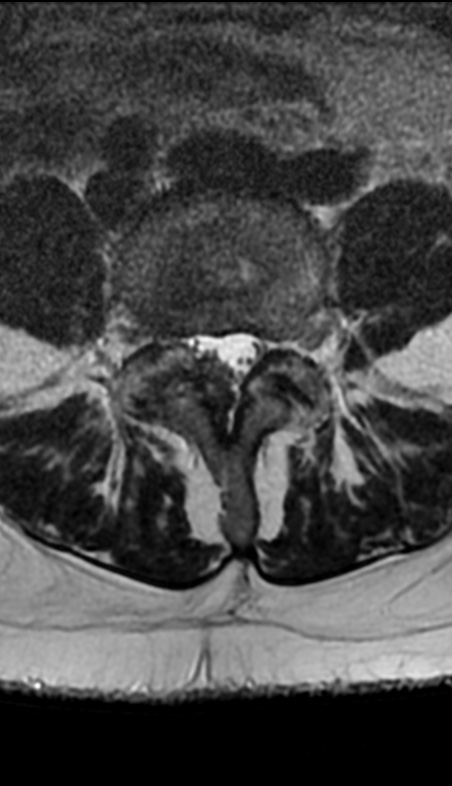

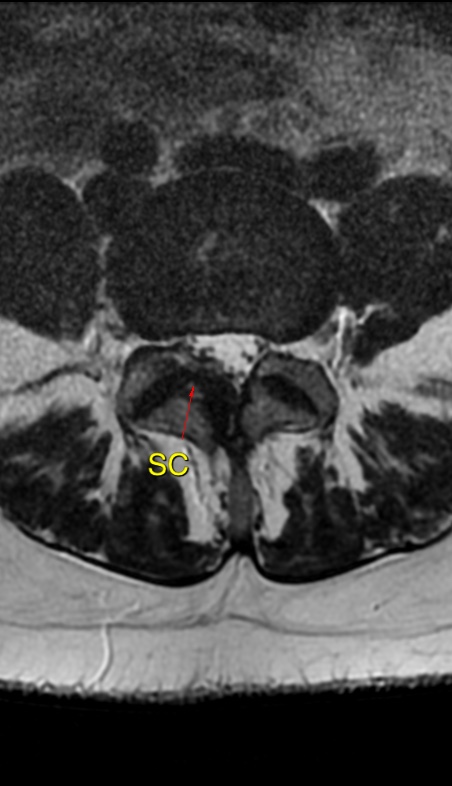

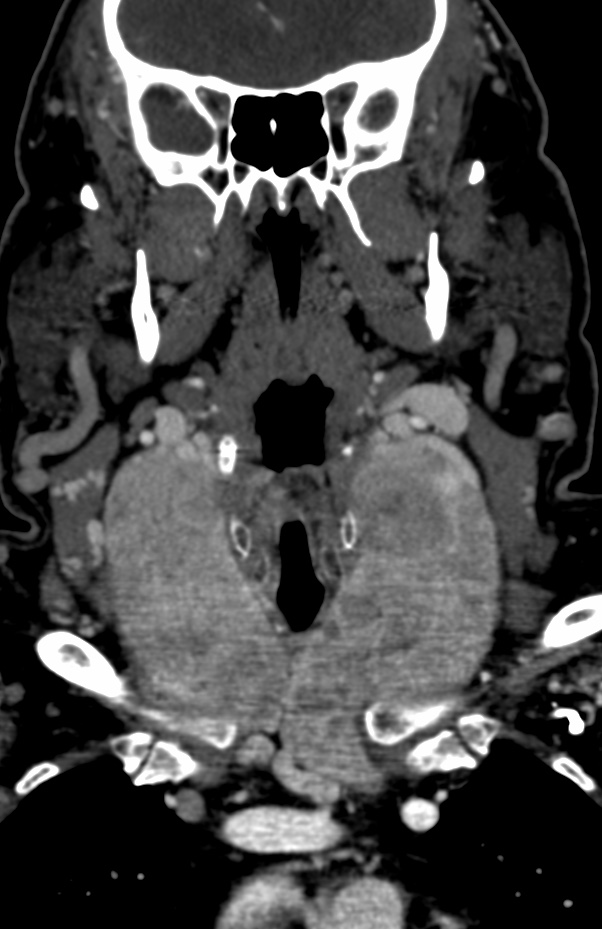

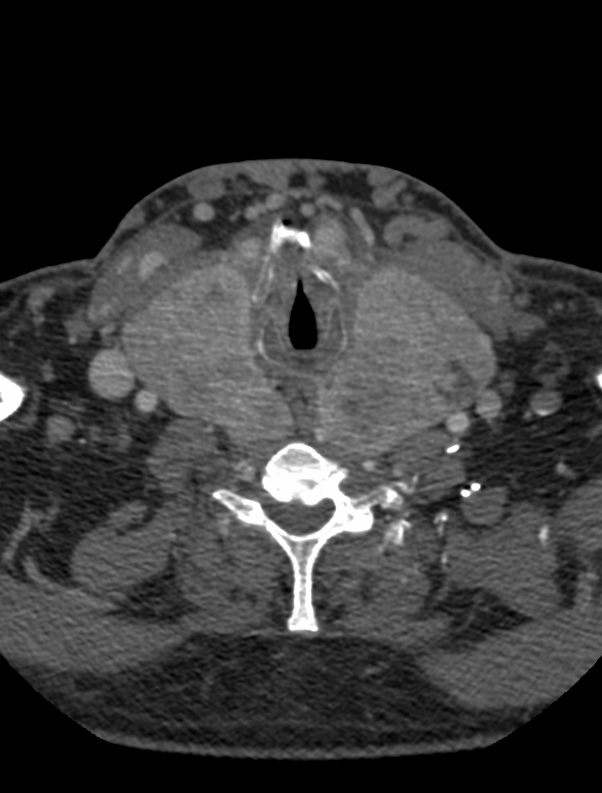

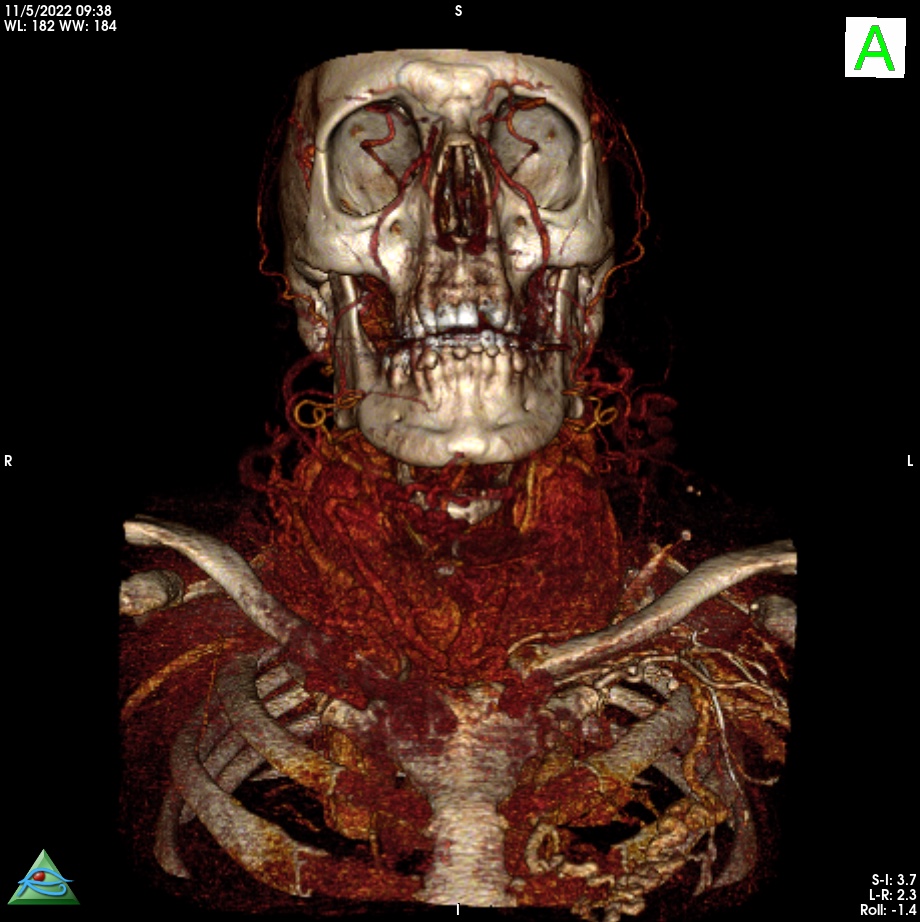

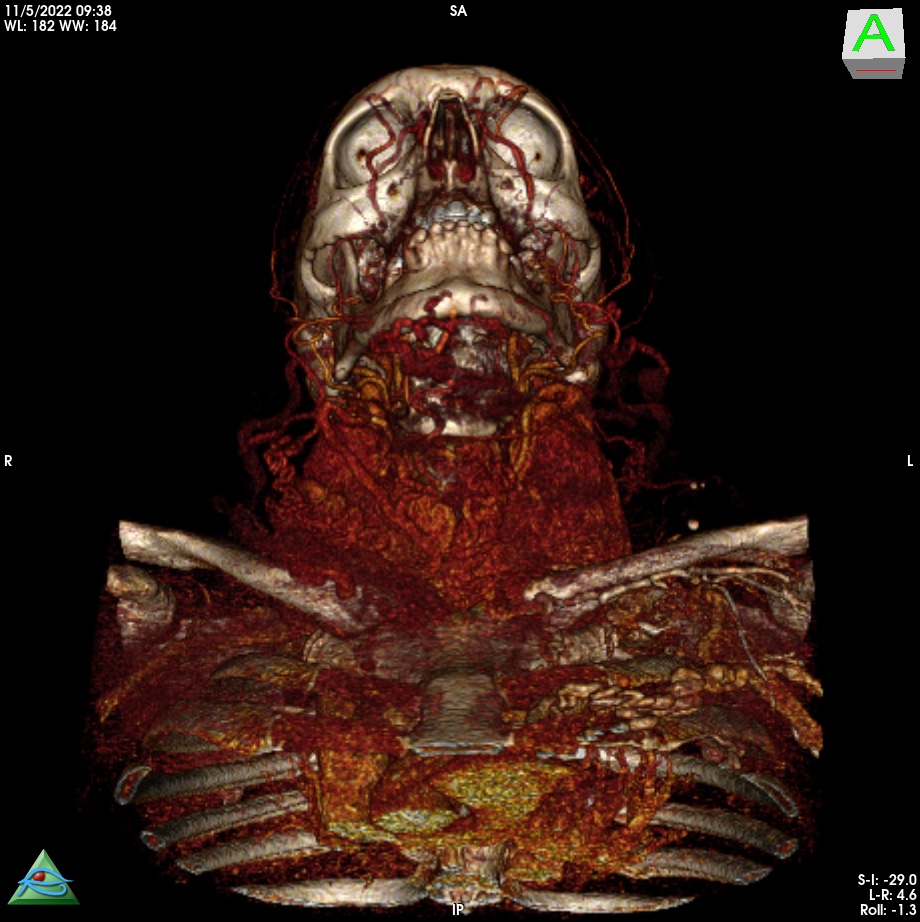

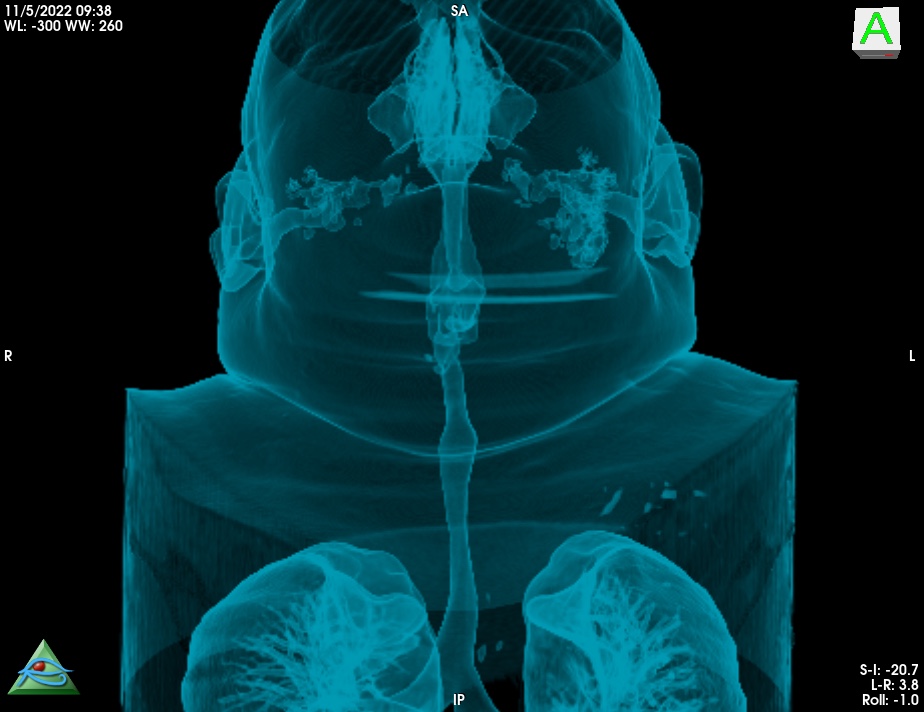

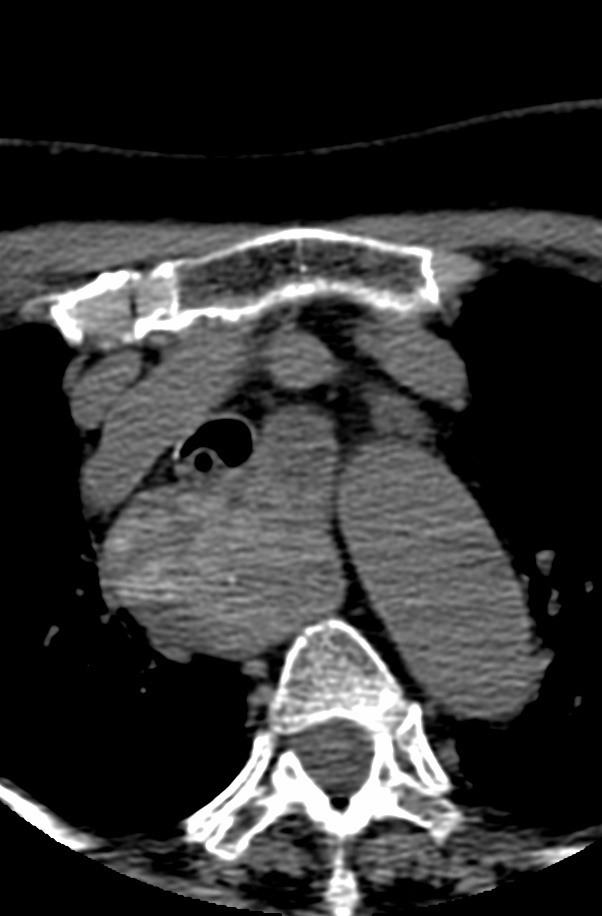

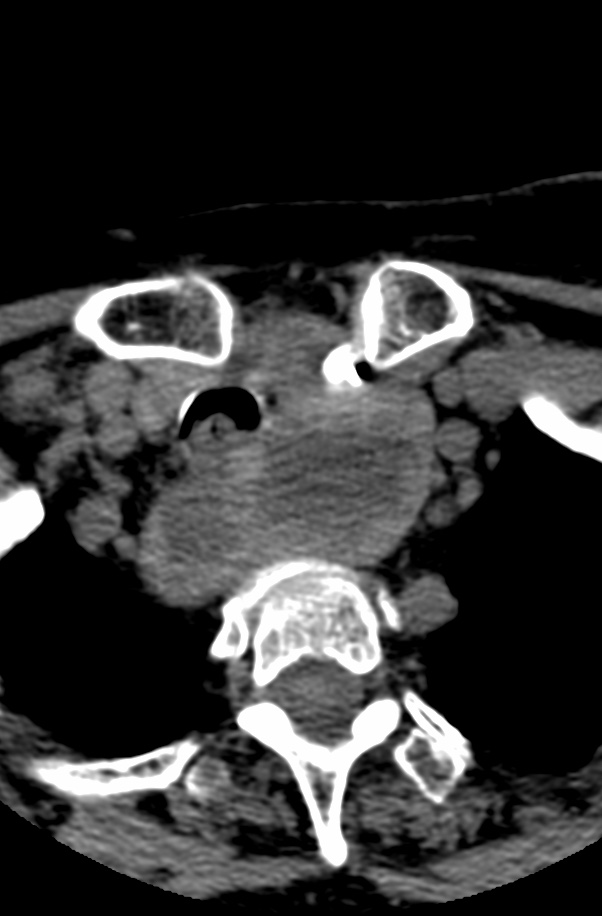

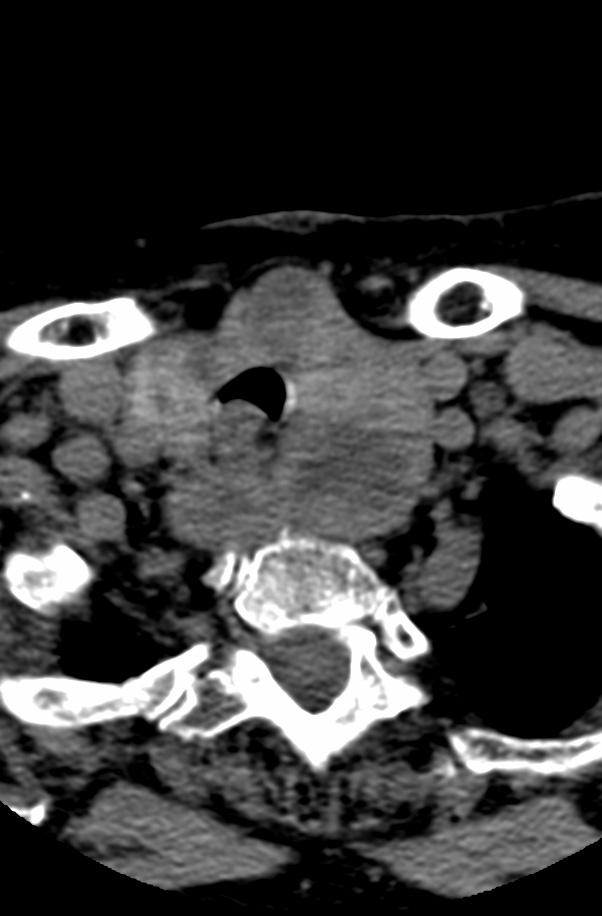

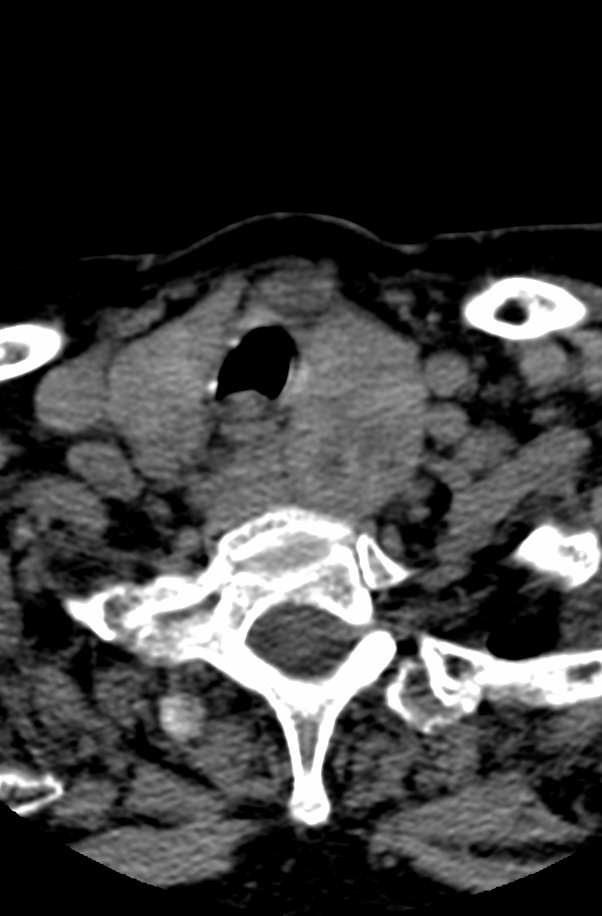

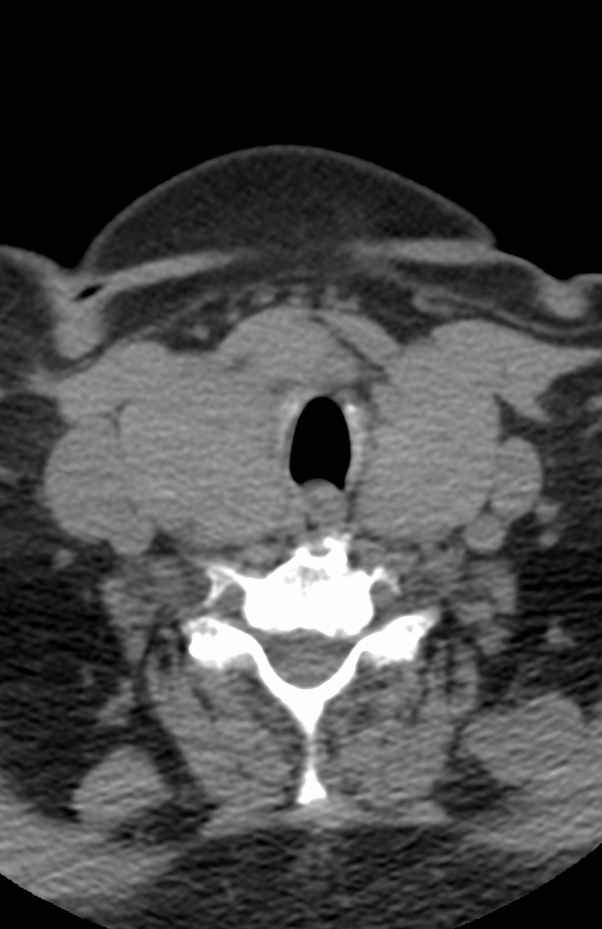

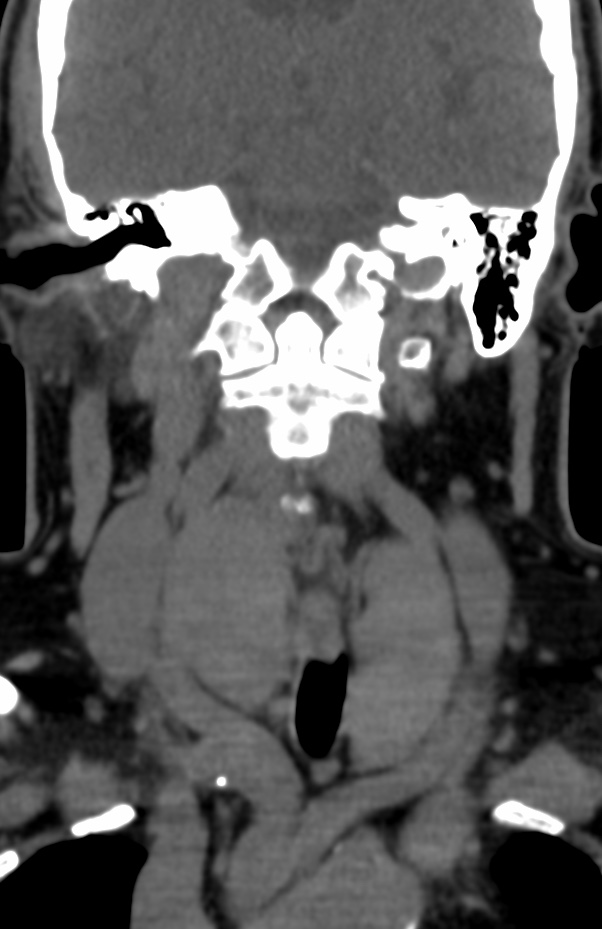

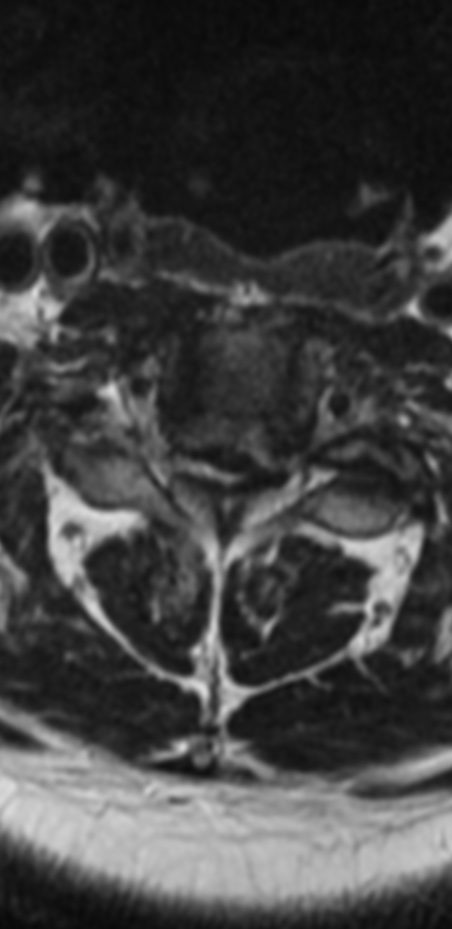

MRI: Canal space of less than 10 mm indicates stenosis. Best to evaluate cord and disk space. Of note, up to 19% of asymptomatic patients have major cervical abnormalities which can be misleading. An MRI is imperative to evaluate spine pathologies. Compression and signal changes on T1 and T2 are indicative of myelopathy pathologies.

Cervical spondylotic myelopathy will frequently involve compression of the lateral corticospinal tracts resulting in voluntary skeletal muscle control, and the spinocerebellar tracts proprioception. Together, these deficits are responsible for the wide-based spastic gait with clumsy upper extremity function that is classic to cervical myelopathy. Additional commonly involved spinal cord regions are the spinothalamic tracts, which are responsible for contralateral pain and temperature sensation, the posterior columns, which are responsible for the ipsilateral position and vibration sense, and the dorsal nerve root, which is responsible for dermatomal sensation

Reference: